Bart Beaty’s study of 1960s-era Archie Comics, Twelve-Cent Archie, came out two years ago, but with the squeaky-clean icons turned into the soapy hit TV series Riverdale, Rutgers University Press has reissued it with full-color illustrations, so anyone who ever enjoyed the comics no longer has an excuse against buying this milestone in pop-culture criticism. While my eyes appreciate the upgrade, my heart is certain that the book was fantastic even in black and white. Unlike, well, every other academic work I’ve read, Beaty has divided his into 100 tight, concise chapters, and then seemingly threw them into the air and let gravity decide the order. The genius of this approach is that it absolutely works. Whether dissecting the literal shape of panels or discussing whether Archie would be better off with Betty or Veronica (mathematics provides the answer, hilariously), Beaty never fails to enlighten as he charms. I haven’t so much as touched an Archie comic book since leaving grade school, yet every page held me rapt.

Bart Beaty’s study of 1960s-era Archie Comics, Twelve-Cent Archie, came out two years ago, but with the squeaky-clean icons turned into the soapy hit TV series Riverdale, Rutgers University Press has reissued it with full-color illustrations, so anyone who ever enjoyed the comics no longer has an excuse against buying this milestone in pop-culture criticism. While my eyes appreciate the upgrade, my heart is certain that the book was fantastic even in black and white. Unlike, well, every other academic work I’ve read, Beaty has divided his into 100 tight, concise chapters, and then seemingly threw them into the air and let gravity decide the order. The genius of this approach is that it absolutely works. Whether dissecting the literal shape of panels or discussing whether Archie would be better off with Betty or Veronica (mathematics provides the answer, hilariously), Beaty never fails to enlighten as he charms. I haven’t so much as touched an Archie comic book since leaving grade school, yet every page held me rapt.

In Comic Book Film Style: Cinema at 24 Panels Per Second, Canada-based Dru Jeffries argues — rightly, successfully — that the media continues to misuse the term “comic book” as it relates to the movies, in part because it’s bandied about so carelessly, it’s applied even when the source material isn’t a comic book at all. So what is the comic book film, exactly? Jeffries is glad you asked! Per chapter one of his University of Texas Press paperback, the mostly forgotten 2010 actioner The Losers best represents the true definition, in translating the page to the screen as faithfully as possible — not merely in story, but also in style — and the accompanying images from both mediums prove the point, over and over. Subsequent chapters loosen up a bit to examine more flicks, whether through their use of onscreen onomatopoeia (1966’s Batman: The Movie), framing to replicate panels (Creepshow) or manipulation of time (300). Although smartly designed and more than generously illustrated, the book can grow dry if approached from a casual standpoint. So don’t! This material would kill in a classroom setting.

In Comic Book Film Style: Cinema at 24 Panels Per Second, Canada-based Dru Jeffries argues — rightly, successfully — that the media continues to misuse the term “comic book” as it relates to the movies, in part because it’s bandied about so carelessly, it’s applied even when the source material isn’t a comic book at all. So what is the comic book film, exactly? Jeffries is glad you asked! Per chapter one of his University of Texas Press paperback, the mostly forgotten 2010 actioner The Losers best represents the true definition, in translating the page to the screen as faithfully as possible — not merely in story, but also in style — and the accompanying images from both mediums prove the point, over and over. Subsequent chapters loosen up a bit to examine more flicks, whether through their use of onscreen onomatopoeia (1966’s Batman: The Movie), framing to replicate panels (Creepshow) or manipulation of time (300). Although smartly designed and more than generously illustrated, the book can grow dry if approached from a casual standpoint. So don’t! This material would kill in a classroom setting.

So venerated is Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 existential sci-fi epic that you could fill a small shelf with books dedicated to the film. Even more are on the way; in the meantime, here’s another! From McFarland & Company, film critic Joe R. Frinzi’s Kubrick’s Monolith: The Art and Mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey reads less like a serious study of the picture (although that exists in one chapter) and more like a Fodor’s guidebook. With enthusiasm and efficiency, Frinzi covers how Arthur C. Clarke’s short story turned into what now is a classic, but considered a failure in its day; plus 2001’s needle-drop soundtrack of classical cuts; Oscar-winning special effects, especially the trippy Star-Gate sequence; and the various sequels, spin-offs and illegitimate children. Chapters vary in usefulness, from quite handy (comparing the various soundtrack albums over the years) to not at all (giving a beat-by-beat plot synopsis). —Rod Lott

So venerated is Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 existential sci-fi epic that you could fill a small shelf with books dedicated to the film. Even more are on the way; in the meantime, here’s another! From McFarland & Company, film critic Joe R. Frinzi’s Kubrick’s Monolith: The Art and Mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey reads less like a serious study of the picture (although that exists in one chapter) and more like a Fodor’s guidebook. With enthusiasm and efficiency, Frinzi covers how Arthur C. Clarke’s short story turned into what now is a classic, but considered a failure in its day; plus 2001’s needle-drop soundtrack of classical cuts; Oscar-winning special effects, especially the trippy Star-Gate sequence; and the various sequels, spin-offs and illegitimate children. Chapters vary in usefulness, from quite handy (comparing the various soundtrack albums over the years) to not at all (giving a beat-by-beat plot synopsis). —Rod Lott

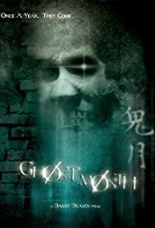

In

In

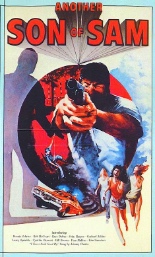

If David Berkowitz, the real-life Son of Sam, actually did receive his orders to kill from a dog, that would make more sense than

If David Berkowitz, the real-life Son of Sam, actually did receive his orders to kill from a dog, that would make more sense than

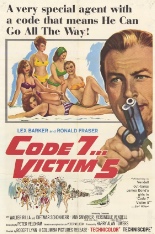

Watching

Watching