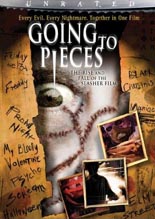

Slasher films are targets of scorn from critics and other high-minded pillars of the community, yet a nonstop source of fun for movie buffs. Adam Rockoff’s 2002 critical study, Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978-1986, stands as the definitive guide to this subgenre — extremely well-written and well-researched, with neither a dry spot nor scholarly leaning within its pages.

Slasher films are targets of scorn from critics and other high-minded pillars of the community, yet a nonstop source of fun for movie buffs. Adam Rockoff’s 2002 critical study, Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978-1986, stands as the definitive guide to this subgenre — extremely well-written and well-researched, with neither a dry spot nor scholarly leaning within its pages.

The same can be said for the resulting documentary, Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, whose title drops the text’s range of years addressed.

In the book, Rockoff (more recently, author of The Horror of It All) is quick to defend his beloved slashers, making a good point about how tame they are violence-wise when compared to the body count of the 1980s’ testosterone-overdosed actioners like Commando and Rambo III.

Better yet, he’s honest; as willing as he is to call John Carpenter’s Halloween a classic (and it is), he’s just as willing to call a stinker a stinker (and there are more than a few). By interviewing some of the principals behind the screen’s seminal slashers — and even some comparatively fringe ones — Rockoff gives us a detailed and eye-opening all-access pass into some juicy, behind-the-scenes stories. And who knew there were any such tales to be told regarding Terror Train, Happy Birthday to Me or My Bloody Valentine?

Better yet, he’s honest; as willing as he is to call John Carpenter’s Halloween a classic (and it is), he’s just as willing to call a stinker a stinker (and there are more than a few). By interviewing some of the principals behind the screen’s seminal slashers — and even some comparatively fringe ones — Rockoff gives us a detailed and eye-opening all-access pass into some juicy, behind-the-scenes stories. And who knew there were any such tales to be told regarding Terror Train, Happy Birthday to Me or My Bloody Valentine?

The documentary seems practically lifted from the pages, with the added benefit of bloody footage from the films being discussed. (It’s one thing to read about Sleepaway Camp’s disturbing twist ending, but another thing altogether to see the damned thing.) In addition to the heavy-hitters, the B- and C-titles like those above are given equal time, making them appear even more watchable than they actually are in full. Although the filmmakers — that includes Rockoff, who scripted — deserve credit for seeking out so many on-camera participants, I only wish they wouldn’t have employed the annoyingly pretentious device of having them walk while talking to us viewers.

From the slashers’ early days of Psycho to its post-modern parody days of Scream and Scary Movie (and, in the doc, the then-current revival with the likes of Saw and Hostel), Rockoff has all the gory bases covered. If Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees and Freddy Krueger are your idea of a good time, his book was written just for you. Oh, and ditto the doc. —Rod Lott