If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.

If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.

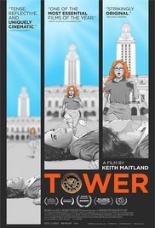

Tower, Keith Maitland’s Indiegogo-funded documentary, admirably upends that narrative. Through a radical mix of archival footage, rotoscopic re-enactments and firsthand accounts, the Austin, Texas-based filmmaker chronicles the day’s events through the words of basically everyone but the shooter — people like Aleck Hernandez Jr. (Aldo Ordoñez), a teenage paperboy shot on his route; officers Houston McCoy (Blair Jackson, Varsity Blood) and Ramiro Martinez (Louie Arnette, #Slaughterhouse), who ultimately killed Whitman in a standoff; and Claire Wilson (Violett Beane, TV’s The Flash), an 18-year-old anthropology student who lost both her fiancé, Tom Eckman (Cole Bee Wilson) and her unborn baby.

Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.

Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.

The animation, equal parts dazzling and distracting, doesn’t serve much purpose beyond the visual replication of what wasn’t captured on camera in ’66 (amazingly, though, a lot was). But even if these spritzes of eye candy seem garish next to the gritty historical footage, Maitland’s inventive approach to tragedy and storytelling make Tower essential to our understanding of what really goes on during the panic and chaos of mass shootings, and serves as a poignant reminder of the heroism we don’t often remember. It might not tell the whole story, but it tells the ones that needed to be heard. —Zach Hale

So much of modern horror has been reduced to a series of cheap jumps and contrived shock-value tactics, a trend 20 years or so in the making that managed to suck a lot of the life out of a once artful ilk. The genre arguably peaked in the late ’70s and early ’80s with heavily stylized, blood-curling flicks like Dario Argento’s

So much of modern horror has been reduced to a series of cheap jumps and contrived shock-value tactics, a trend 20 years or so in the making that managed to suck a lot of the life out of a once artful ilk. The genre arguably peaked in the late ’70s and early ’80s with heavily stylized, blood-curling flicks like Dario Argento’s