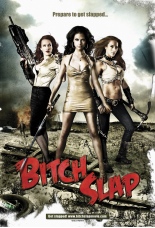

The one thing you have to know about the misunderstood masterpiece that is Bitch Slap is that you shouldn’t go into it expecting to see a whole lotta nipples. You will see at least two (by my count), but since they don’t belong to any of the three scorchingly hot protagonists, many confused genre enthusiasts have chosen to denounce the film as a failure.

The one thing you have to know about the misunderstood masterpiece that is Bitch Slap is that you shouldn’t go into it expecting to see a whole lotta nipples. You will see at least two (by my count), but since they don’t belong to any of the three scorchingly hot protagonists, many confused genre enthusiasts have chosen to denounce the film as a failure.

They are morons. Do not listen to them. Instead, do what I did and listen only to the rock-hard, throbbing critic in your pants. Seriously, if you can make it through Bitch Slap without having to adjust yourself in order to accommodate a prolonged and painful tightness, you’re either a eunuch, a girl, a homosexual or so incredibly and specifically jaded in your perversions, the only chance of finding what you need can be found at www.balloonpoppingplushymilfsquirters.com. It’s the purest form of cinematic Viagra I’ve ever seen, and the fact that it achieves this distinction without overdosing on nips and pubes should be praised, not derided.

A joyous pastiche of all that is great about genre cinema, Bitch Slap essentially plays like a greatest-hits collection of all your favorite movies from Memento and The Usual Suspects to Kill Bill and Sin City, ad infinitum. But most of all, the film is a celebration of the badass femme fatales best epitomized by Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

A joyous pastiche of all that is great about genre cinema, Bitch Slap essentially plays like a greatest-hits collection of all your favorite movies from Memento and The Usual Suspects to Kill Bill and Sin City, ad infinitum. But most of all, the film is a celebration of the badass femme fatales best epitomized by Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

The plot is essentially unimportant — a slender thread upon which to hang its vast collection of references and homages — but the cast is key to the flick’s success. As its trio of dangerous vixens, Julia Voth, Erin Cummings and America Olivo will sear themselves permanently into your consciousness, each one representing a different kind of archetypal hotness. Voth plays the doe-eyed innocent, trapped in the body of the world’s sexiest stripper; Cummings is the calm, voluptuous professional, dressed to kill in a pencil skirt and fishnets; and Olivo is the psychotic hothead in the tight leather pants with the killer abs. Whatever your personal kink, one of them is guaranteed to linger in your dreams.

Unless you only get off on blondes. In which case, you can go fuck yourself. —Allan Mott

This is a great idea — the chance for an Americanized

This is a great idea — the chance for an Americanized

Isn’t statutory rape hilarious? No? Agreed. Tell that to

Isn’t statutory rape hilarious? No? Agreed. Tell that to  Although they both proclaim to love one another deeply, their time apart is the beginning of the end. And good for him, because no sex would be worth being hitched to someone as brick-stupid as Lola. As Jim Dale’s theme song goes, she’s “pretty crazy, dizzy as a daisy,” with a squeaky voice that makes Teresa Ganzel seem like a Rhodes Scholar by comparison. “Darling, what’s a Puerto Rican?” asks Lola, who literally can’t remember how to look before crossing the street.

Although they both proclaim to love one another deeply, their time apart is the beginning of the end. And good for him, because no sex would be worth being hitched to someone as brick-stupid as Lola. As Jim Dale’s theme song goes, she’s “pretty crazy, dizzy as a daisy,” with a squeaky voice that makes Teresa Ganzel seem like a Rhodes Scholar by comparison. “Darling, what’s a Puerto Rican?” asks Lola, who literally can’t remember how to look before crossing the street.

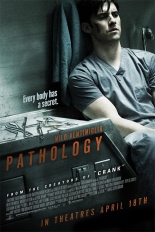

There’s not a single likable character in Marc Schölermann’s

There’s not a single likable character in Marc Schölermann’s  But, wait, there’s more! They also engage in group activities like smoking crack and having sex on the slabs. Why? The only good reason I can think of is because this was written by the reigning kings of over-the-top cinema, Neveldine/Taylor, who wrote and directed the

But, wait, there’s more! They also engage in group activities like smoking crack and having sex on the slabs. Why? The only good reason I can think of is because this was written by the reigning kings of over-the-top cinema, Neveldine/Taylor, who wrote and directed the