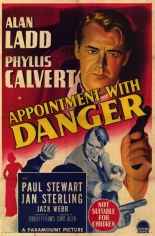

Appointment with Danger is one of those movies that come along every so often: one from which you don’t expect more than a mildly diverting 89 minutes, but turns out to be a small gem. The cast includes Alan Ladd and some favorite character actors — Jack Webb, Harry Morgan, Paul Stewart, Jan Sterling — that I’d like to kick back and have a beer with. The picture was credited as being film noir, so why not take a chance?

Appointment with Danger is one of those movies that come along every so often: one from which you don’t expect more than a mildly diverting 89 minutes, but turns out to be a small gem. The cast includes Alan Ladd and some favorite character actors — Jack Webb, Harry Morgan, Paul Stewart, Jan Sterling — that I’d like to kick back and have a beer with. The picture was credited as being film noir, so why not take a chance?

Ladd is Al Goddard, a postal inspector no one likes, sent to Gary, Ind., to investigate the murder of one of his colleagues. He finds that the only witness is a nun, Sister Augustine (Phyllis Calvert). As soon as they meet, you suspect that he will end up carrying an unlightable torch for her, but it doesn’t happen. They are both too dedicated to their jobs for such foolishness. Besides, she’s already married.

She saw only one of the killers (Morgan), but the other one (Webb) thinks she should be killed just to be on the safe side. Goddard goes undercover as a bent government man in order to find out what these crooks are up to, and how to stop it.

She saw only one of the killers (Morgan), but the other one (Webb) thinks she should be killed just to be on the safe side. Goddard goes undercover as a bent government man in order to find out what these crooks are up to, and how to stop it.

The pleasure comes from the obvious fun the cast is having and the surprisingly sharp dialogue, like Goddard defining love as the feeling a man has for a gun that doesn’t jam, and later, a great line perfectly delivered. When the crooks capture the nun, they decide to kill her, then Goddard talks them out of it and one of them turns to her and says, “Sister, you’re either very lucky or you’ve been living right.” To a nun, he says this, and no one onscreen reacts, despite the fact that it’s the dumbest thing they’ve ever heard. —Doug Bentin

1. prostitute,

1. prostitute,

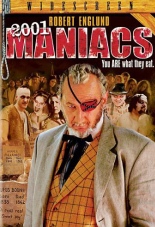

Writer/director Tim Sullivan knows exactly what he’s doing with

Writer/director Tim Sullivan knows exactly what he’s doing with  That’s because, of course, they’re to be the main course of the barbecue for this cannibal clan. Via Buckman’s bevy of busty beauties, the boys succumb to their comely charms, only to end up on the business end of machines of torture. This allows Sullivan to go whole-hog in updating Lewis’ brand of Southern-fried splatter for the gorno generation.

That’s because, of course, they’re to be the main course of the barbecue for this cannibal clan. Via Buckman’s bevy of busty beauties, the boys succumb to their comely charms, only to end up on the business end of machines of torture. This allows Sullivan to go whole-hog in updating Lewis’ brand of Southern-fried splatter for the gorno generation.

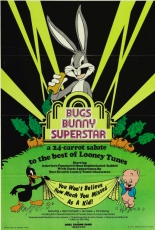

It’s possible to be a movie lover and not like Greta Garbo or John Wayne or Humphrey Bogart, and still retain some credibility — but turn your nose up at Bugs Bunny and hell hath no depth too deep for you, you humorless poseur.

It’s possible to be a movie lover and not like Greta Garbo or John Wayne or Humphrey Bogart, and still retain some credibility — but turn your nose up at Bugs Bunny and hell hath no depth too deep for you, you humorless poseur.  It’s this material, most of which is spoken by one of Bugs’ papas, Bob Clampett, that generated some hurt feelings when this film was released. Co-creators Avery and Friz Freleng are also interviewed, and while Clampett had complimentary things to say about Chuck Jones, Jones — who could nurse a grudge like Silas Marner could nurse a nickel — accused Clampett of being a credit hog. The thing is, when this picture was made, almost everyone from the days of classic animation was looking for credit for the work he’d done for hire in the 1930s-1950s, so a lot of exaggeration was going around.

It’s this material, most of which is spoken by one of Bugs’ papas, Bob Clampett, that generated some hurt feelings when this film was released. Co-creators Avery and Friz Freleng are also interviewed, and while Clampett had complimentary things to say about Chuck Jones, Jones — who could nurse a grudge like Silas Marner could nurse a nickel — accused Clampett of being a credit hog. The thing is, when this picture was made, almost everyone from the days of classic animation was looking for credit for the work he’d done for hire in the 1930s-1950s, so a lot of exaggeration was going around.