With movies, as with potential mates, everyone has a type toward which he or she instinctively gravitates. For me, it’s heists or spiders. For Thomas Kent Miller, it’s that angry red planet — a lifelong fascination that culminates in the publication of the book Mars in the Movies: A History.

With movies, as with potential mates, everyone has a type toward which he or she instinctively gravitates. For me, it’s heists or spiders. For Thomas Kent Miller, it’s that angry red planet — a lifelong fascination that culminates in the publication of the book Mars in the Movies: A History.

Released by McFarland & Company, the trade paperback surveys nearly 100 Mars flicks, roughly from the 1910 Thomas Edison silent short A Trip to Mars to 2015’s blockbuster The Martian. With the latter making a mint and taking seven Oscar nominations, you’d think Miller would find Ridley Scott’s populist smash to be a source of unending joy. Instead, he had “zero emotional response to the film. When I should have felt elated, I felt nothing.” And that call-’em-as-I-see-’em approach is all part of the book’s hours of fun.

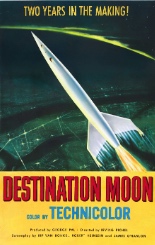

Miller discusses each movie (and the occasional television miniseries), dividing them up among several themed sections: everything pre-Destination Moon, voyages to Mars, invasions from Mars, life on Mars, War of the Worlds adaptations and sequels, comedies, spoofs and, finally, the handful of post-Martian projects. The aforementioned Destination Moon, a 1950 George Pal production, earns its own chapter because the author places it on a pedestal of influence, arguing that only Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey have affected and altered the science-fiction genre as much.

Whether you share that opinion, Miller makes quite the case for it. Throughout the book, readers will notice how he holds these movies accountable for their science. This makes sense since he used to work for NASA, which sometimes, he fully acknowledges, puts him at odds with the mainstream view — most notably in the cases of The Martian and 2005’s War of the Worlds, the Steven Spielberg/Tom Cruise pairing he finds to be such “an onslaught of negative energy” that he is “astonished” it found such critical and commercial favor. Again, reading him getting so worked up only contributes to the enjoyment.

Whether you share that opinion, Miller makes quite the case for it. Throughout the book, readers will notice how he holds these movies accountable for their science. This makes sense since he used to work for NASA, which sometimes, he fully acknowledges, puts him at odds with the mainstream view — most notably in the cases of The Martian and 2005’s War of the Worlds, the Steven Spielberg/Tom Cruise pairing he finds to be such “an onslaught of negative energy” that he is “astonished” it found such critical and commercial favor. Again, reading him getting so worked up only contributes to the enjoyment.

And Mars in the Movies, despite the sourness I’ve highlighted, is enjoyable — even greatly so. I don’t wish to give the impression that reading the book is akin to watching the old man across the street screaming at kids to get off his lawn. From the Flash Gordon serials to Disney’s epic John Carter flop, from the beloved to the obscure, Miller holds great love for the genre and many of the films featured. If there was not already a book on this subject, there needed to be one. Miller has written it — and the definitive one at that … even if his take on 1962’s Battle Beyond the Sun may be the only I’ve ever read that failed to mention how Francis Ford Coppola’s inserted monsters look like a penis and a vagina. —Rod Lott

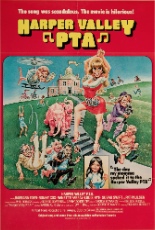

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

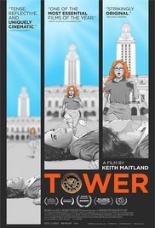

If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.

If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.  Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.

Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.

No tombs exist in Jess Franco’s

No tombs exist in Jess Franco’s  Collective weekend plans of fun in the sun (and sack) go awry when the child disappears from his bedroom, with a ransom note demanding 2 million pesos left in his place. Given the heavy privacy of and limited access to the island, the culprit must be among the 10 or so people sleeping under Annette’s roof — perhaps even Annette herself. But who? And why?

Collective weekend plans of fun in the sun (and sack) go awry when the child disappears from his bedroom, with a ransom note demanding 2 million pesos left in his place. Given the heavy privacy of and limited access to the island, the culprit must be among the 10 or so people sleeping under Annette’s roof — perhaps even Annette herself. But who? And why?