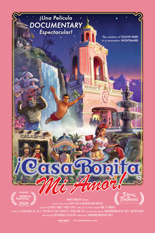

In the department of “Careful what you wish for, because you just might get it … provided you’re willing to part with $40 million,” we have ¡Casa Bonita Mi Amor! The documentary follows South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone — but mostly Parker — as they save the Denver, Colorado-area restaurant from extinction following its COVID-hurled bankruptcy.

Rescuing Casa Bonita is the easy part; restoring it to the beloved kitsch eatery of their childhood memories is another. After all, Casa Bonita — actually started in Oklahoma City, which the doc ignores — was renowned not for its Mexican food, but its amusement park touches, from cliff divers and a built-in haunted cave to a gorilla on the loose. Parker and Stone seek to add their own ideas as well, like an animatronic bird that poops bad fortunes. Which is all fine and good, except the building of “beans and chorine” turns out to be a rotted money pit of disrepair and disaster — some potentially lethal.

Captured by How’s Your News? director Arthur Bradford, a frequent collaborator of Parker and Stone, ¡Casa Bonita Mi Amor! is largely a contractor’s remodelmentary; aside from the F-bombs, the piece could be mistaken for any renovation hour on HGTV. That’s not necessarily a knock, unless you’re expecting a story as wild and crazy as, say, Class Action Park. Given the famous backers at play here, you might.

But you might also be surprised how sad the doc becomes in its final minutes, as reality catches up to Parker. The turn may qualify as too-little-too-late, but anyone standing in their middle-age era will recognize the folly of chasing your past … the ennui of life passing you by … the acknowledgment of your impending doom …

Anyway, who’s ready for sopapillas? —Rod Lott