We like what we like. No excuses necessary. So says Katharine Coldiron in her new book, Junk Film: Why Bad Movies Matter. One need not explain to others why your tastes lean toward X instead of Y, yet I’m glad she’s chosen to do so in the baker’s dozen of essays making up this Castle Bridge Media trade paperback. Pleasure lives on every page.

We like what we like. No excuses necessary. So says Katharine Coldiron in her new book, Junk Film: Why Bad Movies Matter. One need not explain to others why your tastes lean toward X instead of Y, yet I’m glad she’s chosen to do so in the baker’s dozen of essays making up this Castle Bridge Media trade paperback. Pleasure lives on every page.

Whether discussing the merits of Death Bed: The Bed That Eats, the sweat of John Travolta or the litigiousness of Neil Breen, Coldiron’s writing is supremely intelligent. But don’t equate the I word to being an academic slog; the read is a delight. I could see myself having a conversation with her about these movies at a dinner party. And look, if there’s one thing I dread more than social gatherings, it’s talking.

With her wit is as strong as deeming Showgirls screenwriter Joe Eszterhas as “King Shit of Erotic Thriller Mountain,” I’d be more than happy to just listen. As she writes in the book’s introduction, “Without a sense of humor, bad art is unstudiable.”

While she puts that humor to good practice throughout, she takes her subject seriously. A film that fails is worth watching as much as one that succeeds, she argues with conviction. How else can one truly know what makes a movie good without knowing what doesn’t? It’s “an opportunity beyond the obligatory sex and bloodshed, to see something unique and valuable at the purported bottom of the barrel of American cinema.” If I already weren’t aboard that train of thought, her reasoning would win me over.

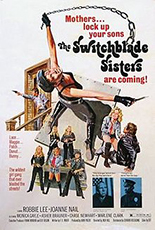

Many of the movies covered, like Jack Hill’s Switchblade Sisters (to which the quote above refers), Coldiron actually adores. Fewer pics repel her, and it’s comforting to find another smart person left baffled by Mark Region’s über-enigmatic After Last Season.

Many of the movies covered, like Jack Hill’s Switchblade Sisters (to which the quote above refers), Coldiron actually adores. Fewer pics repel her, and it’s comforting to find another smart person left baffled by Mark Region’s über-enigmatic After Last Season.

I enjoyed Junk Film so much, I don’t care that two chapters aren’t about movies at all. (They’re on Sean Penn’s atrocious novels and Steven Bochco’s short-lived Cop Rock TV show. Also, they’re hysterical.) Hell, I even learned about an entire eight-film franchise I didn’t know existed: Monogram’s “Teen Agers” films of the late 1940s; her play-by-play rundown of these disposable comedies alone is nearly worth the cover price. Plus, as with Castle Bridge’s Yesterday’s Tomorrows: The Golden Age of Science Fiction Movie Posters, the contents sport expert design from In Churl Yo.

Finally, to address the book’s best-kept secret, Junk Film is actually two books in one, since the piece on Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space was published by UK-based Electric Dreamhouse in 2021 as part of its Midnight Movie Monographs series. Even if that weren’t the case, this remains a real score. —Rod Lott

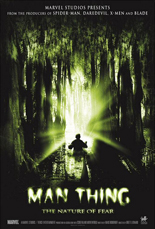

Most of the sequences capture the franchise’s frenetic pace despite the new setting. In lieu of a fruit cellar, Ellie spends a chunk of the film stalking the hallway outside her apartment. The unit door’s peephole sets the stage for a vivid bloodbath that makes the most of the movie’s limited budget. Continually, Evil Dead Rise delivers frights that far outclass movies like

Most of the sequences capture the franchise’s frenetic pace despite the new setting. In lieu of a fruit cellar, Ellie spends a chunk of the film stalking the hallway outside her apartment. The unit door’s peephole sets the stage for a vivid bloodbath that makes the most of the movie’s limited budget. Continually, Evil Dead Rise delivers frights that far outclass movies like

Auld acquaintance should be forgotten, not sniped. Someone in Baltimore failed to get the message, killing 29 celebrants on New Year’s Eve from a downtown perch several stories up. As soon as the authorities determine where, the place explodes, leaving no DNA for them to trace.

Auld acquaintance should be forgotten, not sniped. Someone in Baltimore failed to get the message, killing 29 celebrants on New Year’s Eve from a downtown perch several stories up. As soon as the authorities determine where, the place explodes, leaving no DNA for them to trace.