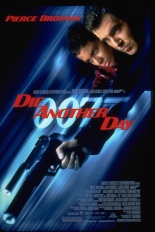

Following the terrible The World Is Not Enough, Pierce Brosnan returned as James Bond in the equally bad Die Another Day, his fourth and final turn as 007. I’d like to think that Madonna skank-tainted this one from the start by providing the wretched theme song that makes Bond fans long for the comparative glory days of a-ha.

Following the terrible The World Is Not Enough, Pierce Brosnan returned as James Bond in the equally bad Die Another Day, his fourth and final turn as 007. I’d like to think that Madonna skank-tainted this one from the start by providing the wretched theme song that makes Bond fans long for the comparative glory days of a-ha.

In the prologue, Bond is captured by Koreans and held prisoner, long enough for Brosnan to grow his hair to its Crusoe lengths of 1997. Then he is traded for a bald-headed Korean named Zao (Rick Yune, The Fast and the Furious), whom the British government held captive — the same guy whose face now is streaked with diamonds, thanks to Bond’s ingenious explosion of a briefcase full of jewels in the aforementioned opening moments.

Then other stuff happens and Halle Berry shows up as an as assassin named Jinx so Bond can bed a black chick, because too many years have passed since he’s done that. And things explode and there’s a swordfight and Madonna appears in a cameo to bring the film to a stop so those watching can go, “Oh, hey, it’s Madonna.” And it culminates at an ice palace with Bond in an invisible car.

Then other stuff happens and Halle Berry shows up as an as assassin named Jinx so Bond can bed a black chick, because too many years have passed since he’s done that. And things explode and there’s a swordfight and Madonna appears in a cameo to bring the film to a stop so those watching can go, “Oh, hey, it’s Madonna.” And it culminates at an ice palace with Bond in an invisible car.

To clarify: an invisible car. With that, the series became all gums, no teeth.

And stupid. Did we really need Berry sassing up the franchise with quips such as “Yo mama!” and “Read this, bitch!” As good as Brosnan was in GoldenEye and Tomorrow Never Dies, his emotional investment appears to have dissipated. Speaking of appearances, in a couple of places during the movie, from certain angles, Brosnan looks just like game show host Chuck Woolery. —Rod Lott

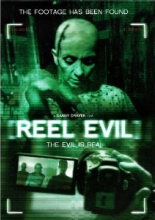

It’s surprising it took this long for Full Moon Features to jump aboard the found-footage bandwagon, since the horror subgenre thrives on an element that is the low-budget production company’s specialty: cheapness.

It’s surprising it took this long for Full Moon Features to jump aboard the found-footage bandwagon, since the horror subgenre thrives on an element that is the low-budget production company’s specialty: cheapness.  Connected by tunnels, the sprawling complex makes for built-in ambience for a backstory of a doctor whose mental patients harbored cannibalistic tendencies. Of course, ghosts of these guys pop in and out, strongly echoing 1999’s

Connected by tunnels, the sprawling complex makes for built-in ambience for a backstory of a doctor whose mental patients harbored cannibalistic tendencies. Of course, ghosts of these guys pop in and out, strongly echoing 1999’s

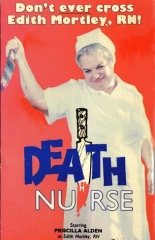

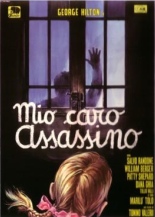

Whoever decreed this rape-revenge with the name of

Whoever decreed this rape-revenge with the name of

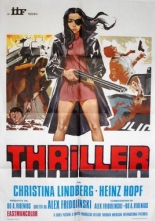

From its first scene set at a rock quarry,

From its first scene set at a rock quarry,  In the process, a black-gloved killer is busy knocking off virtually everyone Peretti questions. Quips a fellow officer, “Soon, they’ll have enough bodies to make up an ice hockey team.”

In the process, a black-gloved killer is busy knocking off virtually everyone Peretti questions. Quips a fellow officer, “Soon, they’ll have enough bodies to make up an ice hockey team.”