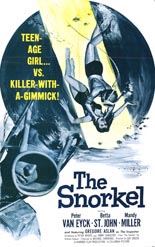

Hammer Films’ The Snorkel opens with a long, silent sequence in which black widower Paul Decker (Peter van Eyck, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse) methodically sets up an elaborate death trap for his wife, apparently drugged into unconsciousness on the couch. After sealing the room shut, he rigs it to flood with natural gas while he lie safely in the crawlspace, accessible via secret door underneath the carpet. He’s in no danger of asphyxiation, thanks to the scuba gear he wears, from which this psychological thriller takes its utterly silly-sounding name. (Even sillier? The credit that reads, “John Holmes’ dog ‘Flush’ as ‘Toto.'”)

Hammer Films’ The Snorkel opens with a long, silent sequence in which black widower Paul Decker (Peter van Eyck, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse) methodically sets up an elaborate death trap for his wife, apparently drugged into unconsciousness on the couch. After sealing the room shut, he rigs it to flood with natural gas while he lie safely in the crawlspace, accessible via secret door underneath the carpet. He’s in no danger of asphyxiation, thanks to the scuba gear he wears, from which this psychological thriller takes its utterly silly-sounding name. (Even sillier? The credit that reads, “John Holmes’ dog ‘Flush’ as ‘Toto.'”)

The deliberate precision Decker takes suggests these steps have become a routine. He has done this before; he knows exactly what he’s doing. And so does director Guy Green (The Magus), for The Snorkel is a superb Hitchcock imitation.

The dead woman’s gangly teenage daughter, Candy (Mandy Miller, The Man in the White Suit), immediately accuses Paul as the killer, beyond a Shadow of a Doubt. She still suspects him of killing her father, too, in a boating “accident” several years prior. Thus, at the core, we have a locked-room mystery in which, privy to the solution from frame one, we’re just waiting for the other characters to catch up.

The dead woman’s gangly teenage daughter, Candy (Mandy Miller, The Man in the White Suit), immediately accuses Paul as the killer, beyond a Shadow of a Doubt. She still suspects him of killing her father, too, in a boating “accident” several years prior. Thus, at the core, we have a locked-room mystery in which, privy to the solution from frame one, we’re just waiting for the other characters to catch up.

How Green manages to wring suspense from that, I’ll never know, especially since we know those characters will, given the times. In ever-noble black and white, The Snorkel presents one of the more perverse methods of murder the screen has seen to date, and that uniqueness — the posters classify it as a “gimmick,” which sounds too William Castle-esque — goes a long way in appeal. It also grants instant menace to van Eyck, who looks so evil and creepy sitting quietly in that apparatus, no acting is necessary. —Rod Lott

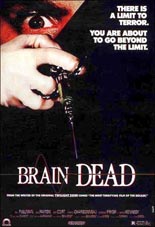

Adam Simon’s

Adam Simon’s

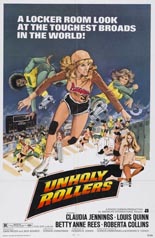

Sick of being sexually harassed by the boss, cat-food factory worker Karen Walker (Claudia Jennings,

Sick of being sexually harassed by the boss, cat-food factory worker Karen Walker (Claudia Jennings,