In the professorial environment of higher ed, the ol’ chestnut is “publish or perish.” It’s not meant to be taken literally. In defense of Dr. Peter Houseman, he doesn’t set out to take it that way.

In the professorial environment of higher ed, the ol’ chestnut is “publish or perish.” It’s not meant to be taken literally. In defense of Dr. Peter Houseman, he doesn’t set out to take it that way.

Played with narcotized indifference by Beyond Darkness’ Gene LeBrock (as Tom Cruise-ian as Peter Facinelli, but with era-apropos feathered hair), Houseman is a Virginia University genetics professor on the verge of creating an anti-aging serum. When the administration threatens to cut his funding if he can’t cough up findings, he skips further studies on monkeys and proceeds directly to introducing modified DNA to his own bloodstream. Using a footlong syringe, he injects the juice through his eyeball, and doesn’t so much as blink or flinch, presumably because he’s a Sexy Faculty Member bursting with testosterone-soaked spermatozoa. Because we’ve seen David Cronenberg’s The Fly, we know things won’t go well.

Directed by George Eastman (screenwriter and star of Joe D’Amato’s Anthropophagus and its Horrible sequel), Metamorphosis doesn’t place The Fly on the Xerox machine as much as it openly copies off its test paper. Subbing for Geena Davis is Catherine Baranov, remarkably adequate for a one-credit actress (and if the Internet Movie Database is to be believed, a waitress at the hotel where the cast and crew slept during the shoot). Look for former Emanuelle Laura Gemser in a bit part as a prostitute overpowered by our truly mad scientist.

Directed by George Eastman (screenwriter and star of Joe D’Amato’s Anthropophagus and its Horrible sequel), Metamorphosis doesn’t place The Fly on the Xerox machine as much as it openly copies off its test paper. Subbing for Geena Davis is Catherine Baranov, remarkably adequate for a one-credit actress (and if the Internet Movie Database is to be believed, a waitress at the hotel where the cast and crew slept during the shoot). Look for former Emanuelle Laura Gemser in a bit part as a prostitute overpowered by our truly mad scientist.

While we’re on the subject on all things overwhelming, the synth-driven score (with occasional cowbell) by Pahamian (aka Women’s Prison Massacre composer Luigi Ceccarelli) is so loud, it possesses the power to drown out dialogue. Worthy of praise, however, is the effects work by Maurizio Trani; a frequent collaborator of Lucio Fulci, Trani provides rather impressive makeup for the metamorphosing Houseman as he ventures from mere Hulk eyes to Sleestak face to … well, you’ll just have to see it. And fans of maniacal-medicine movies should. —Rod Lott

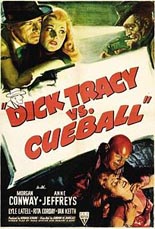

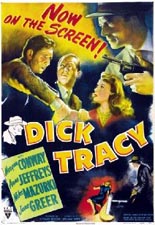

Dick Tracy! Calling Dick Tracy!

Dick Tracy! Calling Dick Tracy!

Ib Melchior’s short story “The Racer” — the source material for 1975’s Roger Corman-produced cult classic

Ib Melchior’s short story “The Racer” — the source material for 1975’s Roger Corman-produced cult classic

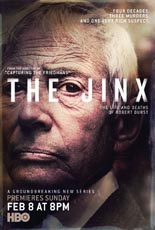

Technically, the year’s finest documentary isn’t even a movie, but a six-episode HBO miniseries:

Technically, the year’s finest documentary isn’t even a movie, but a six-episode HBO miniseries: