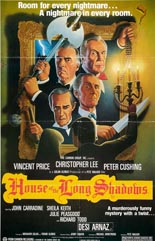

While on a book tour in Great Britain, author Kenneth Magee (Desi Arnaz Jr., 1977’s Joyride) is challenged by his publisher, Sam (Richard Todd, Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright), to write something different from his string of bestselling political thrillers: something epic and all human conditiony, like Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. No prob, says Magee, who bets the Englishman $20,000 that he can turn around a complete manuscript within 24 hours. Ever the gentleman, Sam even offers his client conducive solitude in the House of the Long Shadows, aka Baldpate Manor, a Welsh estate in which no one has resided for 40 years.

While on a book tour in Great Britain, author Kenneth Magee (Desi Arnaz Jr., 1977’s Joyride) is challenged by his publisher, Sam (Richard Todd, Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright), to write something different from his string of bestselling political thrillers: something epic and all human conditiony, like Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. No prob, says Magee, who bets the Englishman $20,000 that he can turn around a complete manuscript within 24 hours. Ever the gentleman, Sam even offers his client conducive solitude in the House of the Long Shadows, aka Baldpate Manor, a Welsh estate in which no one has resided for 40 years.

Magee arrives, predictably, on a dark and stormy night. But for an abode so empty, there sure are a lot of creepy old people lurking about its unlit hallways and stairwells. None should be there; all reek of sinister motives. With so much distraction and danger, the bad news is that Magee looks to lose that bet; the good news is he won’t notice the financial impact, because he’ll be dead.

More prestigious than the average Cannon Films release of the early 1980s, this House finds inspiration in the oft-adapted Broadway classic Seven Keys to Baldpate. It also represents the one and only big-screen meeting of fright-film titans Vincent Price, Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and John Carradine — sort of like an Avengers for the Famous Monsters of Filmland generation. That alone makes Long Shadows worth a look, but don’t expect much to come of your stay.

More prestigious than the average Cannon Films release of the early 1980s, this House finds inspiration in the oft-adapted Broadway classic Seven Keys to Baldpate. It also represents the one and only big-screen meeting of fright-film titans Vincent Price, Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and John Carradine — sort of like an Avengers for the Famous Monsters of Filmland generation. That alone makes Long Shadows worth a look, but don’t expect much to come of your stay.

The final bow for UK cult director Pete Walker (House of Whipcord), the PG-rated production means well in its old-fashioned adherence to the creaky Old Dark House subgenre and all the Gothic trappings that accompany it. Good intentions do not automatically translate into a good movie, and such is the case here, with a mystery that doesn’t try hard enough to pique audience interest and elements of horror defanged enough for telling ’round a Webelos campfire. It’s as if Walker, never one to shy away from sex or violence, was so out of his element with being inoffensive that he overdid the undercooking. Overall shoddy construction is to blame for the “twist” ending being obvious by the film’s second scene. —Rod Lott

In the

In the

In

In

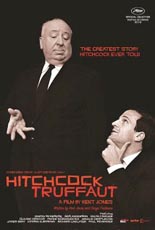

However one pulls off a successful documentary about the making of a book, Kent Jones has done it with Hitchcock/Truffaut. Borrowing its title from the

However one pulls off a successful documentary about the making of a book, Kent Jones has done it with Hitchcock/Truffaut. Borrowing its title from the  Although film cameras ironically were not present for the men’s talks, an audio recorder was; Jones lucks into having their actual voices at his show-don’t-tell disposal, along with a smattering of behind-the-scenes photographs. Without these, the doc would lose what makes it special. He doesn’t rely solely on his subjects, either, opening the floor to such celebrity admirers as Martin Scorsese, David Fincher and Wes Anderson, all avowed fans of the classic book, which has inspired and informed work of their own.

Although film cameras ironically were not present for the men’s talks, an audio recorder was; Jones lucks into having their actual voices at his show-don’t-tell disposal, along with a smattering of behind-the-scenes photographs. Without these, the doc would lose what makes it special. He doesn’t rely solely on his subjects, either, opening the floor to such celebrity admirers as Martin Scorsese, David Fincher and Wes Anderson, all avowed fans of the classic book, which has inspired and informed work of their own.

In

In