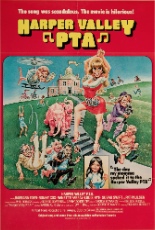

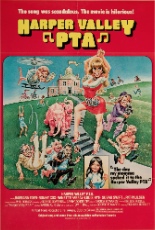

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

Before we get to that triumphant socking, however, let’s remember a better time in cinema where, if you were a country singer who had a good enough song with a good enough narrative, it could be turned into a good enough movie. With titles like Coward of the County, The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia and Take This Job and Shove It, the screenplays practically wrote themselves.

Jeannie C. Riley’s scandalous chart-topper took the country by storm in 1969, but it wasn’t until a decade later when the titular Harper Valley P.T.A. incident finally would make it to the big screen. This was mostly due, I believe, to the dream casting of I Dream of Jeannie’s Barbara Eden, in the middle of a MILF-based career resurgence with every angle framing her as if she stepped right off the set of a latter-day Russ Meyer flick, as the wanton widow Ms. Johnson, who has been seen wearing her mini-skirts way too high.

Sullen daughter Dee (Audrey Rose’s Susan Swift) is sent home with a note from the Harper Valley P.T.A. that says she is going to be suspended if Stella doesn’t start exercising some moderate decorum in both her private and public life. It really doesn’t help things that our introduction to said mom is her brazenly hot-pantsin’ about the living room, pulling tabs off Schlitz cans and singing bawdy 1920s ragtime tunes with her hairdresser and two dudes from the bar she frequents, all the while ignoring the tears of traumatic embarrassment she’s created for her offspring. Maybe the P.T.A. has a point …

Sullen daughter Dee (Audrey Rose’s Susan Swift) is sent home with a note from the Harper Valley P.T.A. that says she is going to be suspended if Stella doesn’t start exercising some moderate decorum in both her private and public life. It really doesn’t help things that our introduction to said mom is her brazenly hot-pantsin’ about the living room, pulling tabs off Schlitz cans and singing bawdy 1920s ragtime tunes with her hairdresser and two dudes from the bar she frequents, all the while ignoring the tears of traumatic embarrassment she’s created for her offspring. Maybe the P.T.A. has a point …

Instead of taking a deep dark look at herself and the environment she’s built for her daughter, Stella embarrassingly marches right up to that board meeting and spills all of the council’s dirty secrets, from light alcoholism and small-time gambling to impregnating secretaries and nymphomaniacal exhibitionism.

And while this is where the song ended, the movie still has an hour and a half to go, so Stella and her hairdresser pal (Nanette Fabray, Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County) pull off various pranks that would eventually be used in every subsequent Police Academy film, from locking someone out of their room naked to replacing a dowdy gossip’s regular shampoo with a very hair-unfriendly product to even some good old-fashioned manure-based shenanigans (bovine feces supplied by “Seattle Slew,” according to the credits).

And while this is where the song ended, the movie still has an hour and a half to go, so Stella and her hairdresser pal (Nanette Fabray, Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County) pull off various pranks that would eventually be used in every subsequent Police Academy film, from locking someone out of their room naked to replacing a dowdy gossip’s regular shampoo with a very hair-unfriendly product to even some good old-fashioned manure-based shenanigans (bovine feces supplied by “Seattle Slew,” according to the credits).

With an all-over-the map plot that has Stella fighting both the illegal foreclosure of her house and election fraud, all the while stopping a bumbling kidnapping in a finale wherein our heroines dress as nuns, Harper Valley P.T.A. is far raunchier than I originally remember it being as kid, with a lot more near-nudity and compromising situations that I’m sure were toned down by the time it was made into a short-lived weekly series on NBC, produced by The Brady Bunch’s Sherwood Schwartz, who amazingly stretched the song’s already tight-pantsed premise into a staggering 30 episodes, which, of course, led to diminishing sockings with each installment. —Louis Fowler

Get it at Amazon.

Producer Irwin Allen kept his once-Towering cinematic credibility in flames with Fire, a virtual remake of his previous year’s telepic Flood — just with another basic concept from your high school chemistry class (or a then-rather popular 1970s R&B-funk band).

Producer Irwin Allen kept his once-Towering cinematic credibility in flames with Fire, a virtual remake of his previous year’s telepic Flood — just with another basic concept from your high school chemistry class (or a then-rather popular 1970s R&B-funk band).  And speaking of Hanging by a Thread, Patty Duke again assumes the role of an unhappy wife, here married — for the moment, at least — to a fellow doctor (Alex Cord, Chosen Survivors). Perhaps their love will be, um, reignited? Dur.

And speaking of Hanging by a Thread, Patty Duke again assumes the role of an unhappy wife, here married — for the moment, at least — to a fellow doctor (Alex Cord, Chosen Survivors). Perhaps their love will be, um, reignited? Dur.

Welcome back to Burkittsville, Maryland! And this time, we really mean it!

Welcome back to Burkittsville, Maryland! And this time, we really mean it!

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you have plenty of stories about the time your mother vehemently told off various local government and educational agencies. And as great as those stories are, they will still never come close to the time that Stella Johnson “socked it” to the Harper Valley Parent-Teacher Association over a minor dress code violation.

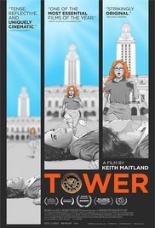

If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.

If you know just one name from the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, it’s probably Charles Whitman, the deranged assailant who gunned down 49 people — killing 14 — in an hour and a half’s time. It’s one of the (many) unfortunate realities of these mass shooting-crazed days: We remember the villains, their horrific acts of violence, but know next to nothing of their victims.  Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.

Forgoing any examination of the massacre’s broader, macro-level impact, Tower instead recounts the poignant internal conflicts of its characters — like the powerless torment of bare skin on blistering pavement, or the cowardice one feels when realizing they lack the courage to help the wounded. All the while, intermittent gunshots ring out in the middle of the sound mix and double down on the unease — an effect that puts you squarely on campus and in the line of fire.