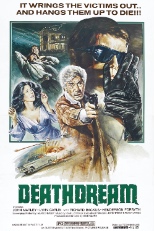

Black Christmas wasn’t the only horror film Bob Clark directed — just the best and most influential. However, let us not allow history to neglect Deathdream, at once an unofficial adaptation of W.W. Jacobs’ classic short story, “The Monkey’s Paw,” and a feverish allegory on the PTSD of our Vietnam vets.

Black Christmas wasn’t the only horror film Bob Clark directed — just the best and most influential. However, let us not allow history to neglect Deathdream, at once an unofficial adaptation of W.W. Jacobs’ classic short story, “The Monkey’s Paw,” and a feverish allegory on the PTSD of our Vietnam vets.

The family of soldier Andy Brooks (Richard Backus, The First Deadly Sin) receives some tragic, not entirely unexpected news: The young man has been killed while fighting the unwinnable war in ’Nam. Hours later, an apparent miracle follows: In the Dead of Night (to borrow Deathdream’s alternate title), Andy appears in the entry hall, as if he’d come marching home.

He seems a bit, well, off, because he’s a member of the walking dead. The Brookses either are too overjoyed to notice or are in denial — perhaps a helping of both. As viewers, we are not privy to scenes of prewar Andy, but certainly he wasn’t always quite this pale or quick to strangle dogs, was he? Unremarked upon, the Scooby-Doo light switch cover in his childhood room serves as a nice contrast to his sinister new ways, and a reminder of the innocence irrevocably lost in the jungle.

Although he ended up writing for daytime soaps, Backus is awfully good as the prodigal son who joined the Army as a boy and left it as a zombie. The movie doesn’t ask him to display, oh, range, yet as his character’s physical body gradually fails him and falls away, Backus need do little more than remain still and slowly turn his all-American smile into an unholy rictus. The more homicidal he becomes, the more horrifying his face, providing Deathdream with most of its shivers.

Although he ended up writing for daytime soaps, Backus is awfully good as the prodigal son who joined the Army as a boy and left it as a zombie. The movie doesn’t ask him to display, oh, range, yet as his character’s physical body gradually fails him and falls away, Backus need do little more than remain still and slowly turn his all-American smile into an unholy rictus. The more homicidal he becomes, the more horrifying his face, providing Deathdream with most of its shivers.

If Andy is one-dimensional — and he is — Clark and scriptwriter Alan Ormsby (Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things) let John Marley play far more shades. Assured a spot in cinema history for being That Guy Who Wakes Next to a Horse’s Head in The Godfather, Marley has this film’s most complex performance as Andy’s father. In many ways, it establishes the template for what Gregory Peck would do a mere two years later in the showier The Omen: Be torn between the allegiance to his only son and the responsibility for ending his bad behavior. His journey encapsulates the punch line of an old Bill Cosby routine: “I brought you into this world and I’ll take you out.”

With a Pepto-Bismol color palette that mirrors the uneasiness of his tale, Clark nails making the most of not a lot. That he did it twice in one calendar year (with Black Christmas following this to theaters about four months later) makes each picture all the more impressive. —Rod Lott

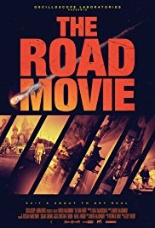

Here now, something you may not mind the Russians for doing:

Here now, something you may not mind the Russians for doing: