Tastes of Horror is the Korean equivalent to Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, in that the anthology film is a feature version of an existing series. The difference here is that Tastes’ half-dozen stories aren’t new, but adapted from the animated show.

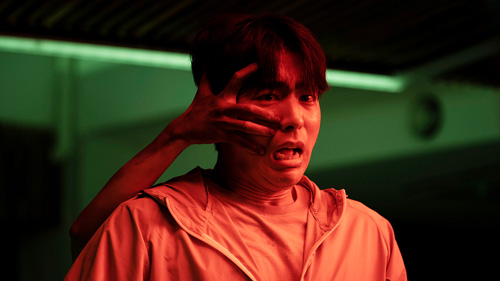

Absent of a wraparound, the segments bump against one another with merely a title card to separate them. In a TikToky take on “The Monkey’s Paw,” aspiring K-poppers encounter a witch’s dance video that, when performed, makes your wish come true. Fresh from winning a casino jackpot, a man is stranded at a strange hotel. Stuck in a purgatorial room, a woman must complete rehab within a specified time to escape.

A girl’s med-school dreams are in danger of being dashed until she learns a sacrifice will earn her good grades. Apartment tenants are warned not to use the building’s gym after hours, but they do, invoking a figure with requisite long, dark hair covering her face. Finally, two mukbang YouTubers face off in a stomach-stuffing eating contest, consuming nauseating piles of donuts, fried chicken, sushi and more.

If these six segments represent the best of Tastes of Horror’s run, I’d hate to see the remainders. All but one put forth an interesting premise, yet sluggish pacing in each fritters that away; the effect is like watching your frugal relative open her gifts verrry carefully so she can save the wrapping paper.

At least visually, the tales feel of a piece, rather than their true origins of coming from five directors. On the other hand, that means Tastes’ “house style” is bland — competent, but bland nonetheless . A few bright spots alight throughout, from clever setups in the gym to a Ringu-inspired nightmare and a sequence of rats raining from the ceiling, yet none enough to push the omnibus into a recommendation. —Rod Lott