One of the more memorable sketches in 1987’s Amazon Women on the Moon comes right before the end credits: A lonely guy named Ray comes home from the video store with an unusual rental: a personalized, POV tape of a super-foxy sex bomb who speaks directly to the camera, dropping his name as she drops her clothes and writhes in bed. Now, expand those five minutes by about 2,000%, don’t play them for laughs, swap the intercourse for conversation — well, most of it — and you have Rent-a-Pal.

One of the more memorable sketches in 1987’s Amazon Women on the Moon comes right before the end credits: A lonely guy named Ray comes home from the video store with an unusual rental: a personalized, POV tape of a super-foxy sex bomb who speaks directly to the camera, dropping his name as she drops her clothes and writhes in bed. Now, expand those five minutes by about 2,000%, don’t play them for laughs, swap the intercourse for conversation — well, most of it — and you have Rent-a-Pal.

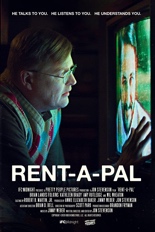

Set in the dawn of the 1990s, Rent-a-Pal gives us a grim look at David (Brian Landis Folkins, The Creep Behind the Camera), a middle-aged beta male in dire need of a companion. Living as a stereotype in the basement of his elderly, invalid mother’s home, he tries video dating, but finds no interested parties. In a moment of despair, he purchases a VHS tape titled Rent-a-Pal from the bargain bin. Its tagline reads, “Meet your new best friend, ‘Andy.’ He talks to you, he listens to you, he understands you.”

They forgot “He manipulates you.”

As played against type by Stand by Me’s Wil Wheaton, Andy asks questions to the watcher, followed by pauses of silence as if listening. For the socially deprived David, it’s enough. He plays the tape until he wears out the heads — and wears on our nerves — because he craves the attachment, however artificial.

As played against type by Stand by Me’s Wil Wheaton, Andy asks questions to the watcher, followed by pauses of silence as if listening. For the socially deprived David, it’s enough. He plays the tape until he wears out the heads — and wears on our nerves — because he craves the attachment, however artificial.

Or is it? Because when David finally meets a woman (Amy Rutledge, Neighbor) who appreciates his company, and vice versa, Andy doesn’t like becoming the proverbial third wheel and makes his opinion known. What writer and first-time director Jon Stevenson does best is not revealing how much of what Andy says comes from the tape or David’s head, leaving it to us to discern. Their friendship is warped and increasingly disturbing, qualifying David for membership in the same cinematic losers’ league as Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle or Jake Gyllenhaal’s Lou Bloom — initially sympathetic characters who test our loyalty as they slide down the spray-butter-slippery slope of deteriorating mental health.

From the start, Folkins earns viewers’ pity, then disdain as he starts screwing up his clear chance at the happiness eluding him for so long. Rutledge is terrific in what is essentially the Rosemarie DeWitt role of the voice of reason, and Wheaton terrifying as either the puppet master behind David’s actions or David’s imagined scapegoat for such. You be the judge. With humor as dark as its tension, Rent-a-Pal isn’t trying to win friends or influence people; the right people will click with its message and see how eerily it holds true today, subbing one technological advance for another. —Rod Lott

In the VHS bonanza,

In the VHS bonanza,  Still, Slash Dance has a little going for it, one being Maranne’s performance. Like her by-the-book cop character, it has a just-the-facts approach that suggests she’s a total pro; whether the movie turns out shoddy, she’s going to treat it as if she were playing both

Still, Slash Dance has a little going for it, one being Maranne’s performance. Like her by-the-book cop character, it has a just-the-facts approach that suggests she’s a total pro; whether the movie turns out shoddy, she’s going to treat it as if she were playing both