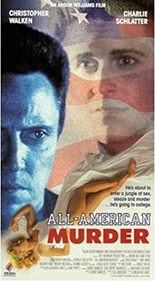

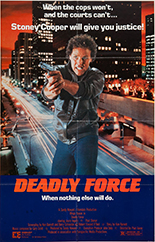

Los Angeles is under the hysteria-ridden spell of a serial killer in what the press dubs “the X Murders” case, so named for the letter left behind in the foreheads of the dead. Per usual in these things, the police are baffled, when a personal connection to victim No. 16 brings back one of their former own — disgraced cop and expert alcoholic Stoney Cooper (Wings Hauser) — from his busy life in New York, playing sidewalk games of rat roulette and bouncing his soccer ball in doggie droppings.

Los Angeles is under the hysteria-ridden spell of a serial killer in what the press dubs “the X Murders” case, so named for the letter left behind in the foreheads of the dead. Per usual in these things, the police are baffled, when a personal connection to victim No. 16 brings back one of their former own — disgraced cop and expert alcoholic Stoney Cooper (Wings Hauser) — from his busy life in New York, playing sidewalk games of rat roulette and bouncing his soccer ball in doggie droppings.

The only person less enthused than LAPD Capt. Hoxley (Lincoln Kilpatrick, 1987’s Prison) to see Stoney in town is his estranged wife, Eddie (Joyce Ingalls, 1975’s The Man Who Wouldn’t Die), now a TV news reporter. However, one of those two will end up boning Stoney in a hammock before the movie calls it quits.

Deadly Force marks a veritable Vice Squad reunion between Hauser, producer Sandy Howard and co-writer Robert Vincent O’Neil (soon to bring us Angel). This doesn’t near the jolt of their ’82 sleaze classic. How could it? As a solo-vehicle attempt to get Wings off the ground, however, it could be worse. With hair that makes William Katt’s look comparatively subtle, Hauser works his baby face to his advantage. His screen presence makes winsome what less-amiable actors might turn into an asshole.

The only point he risks that goodwill is when his sex scene with Ingalls ventures one tongue flick to the nipple too explicit. That move is more unexpected than director Paul Aaron (A Force of One) employing a sub-Magnum P.I. score as an onomatopoeia, but less expected than a cameo by Golden Girl Estelle Getty as a cabbie who’s — get this! — grouchy. —Rod Lott