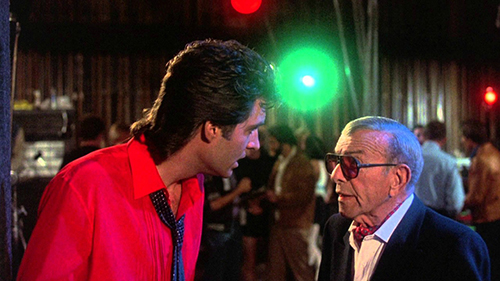

Thanks to the Oh, God! films I grew up with, when I think of the Lord Almighty in his human form, for better or worse, it’s typically in the guise of late comedian George Burns. In the trilogy, he aided grocery store produce manager John Denver, rode in a motorcycle with the single-monikered Louanne and, in his grandest casting ever, battled a doppelgänger devil over Ted Wass’ eternal soul.

Thanks to the Oh, God! films I grew up with, when I think of the Lord Almighty in his human form, for better or worse, it’s typically in the guise of late comedian George Burns. In the trilogy, he aided grocery store produce manager John Denver, rode in a motorcycle with the single-monikered Louanne and, in his grandest casting ever, battled a doppelgänger devil over Ted Wass’ eternal soul.

It’s the third one, Oh, God! You Devil, that casts Burns as his own worst enemy, Satan. But instead of a devil who wants to murder and maim the world over, he instead uses evil to commit rather irritating pranks, usually the kind where someone falls into a wedding cake or pushes a couple of people into a pool.

Going by the name of Harry O. Tophet — “Tophet” is the Hebrew word for “hell,” so kudos on that — he comes across the path of failed songwriter Bobby (Wass, not to be confused with Craig Wasson, a regular mistake of mine), who, as you can guess, wants to make it big. He makes a deal with Tophet for instant stardom.

Being a deal with the devil, things don’t go exactly as Bobby thought. He is inserted into the body of rock star Billy Wayne and, for a while, things are great: fame, fortune and all the threesomes he can handle. Until, of course, he runs into his wife, who has no idea who he is; this meeting has him wanting to back out.

Too bad! As expected, the Prince of Darkness is a total asshole. With about 20 minutes of the film left, Burns enters the film as the deity you’d expect, God. They wager a game of high-stakes cards over Bobby’s soul, with stakes that make me feel a little uneasy.

Having not seen this entry since the constant HBO airings circa 1985, I was surprised by how much I actually liked it, despite it seeming like the cheapest film in an already cheap series. Wass — not Wasson! — is a decent enough foil for these satanic shenanigans, but Burns is likable even as the devil, even if he’s really not that far off from his interpretation of God.

I wonder how the actual God liked these movies though. I don’t want to step on any supernatural toes, mostly for the fear of eternal damnation. —Louis Fowler

Months from now, and even years from now, someone is going to ask if you’ve seen Small Engine Repair. I believe this because it’s exactly the kind of unassuming little film that takes time to find its audience — living through word of mouth, one conversation at a time. So why not just see it right now?

Months from now, and even years from now, someone is going to ask if you’ve seen Small Engine Repair. I believe this because it’s exactly the kind of unassuming little film that takes time to find its audience — living through word of mouth, one conversation at a time. So why not just see it right now?