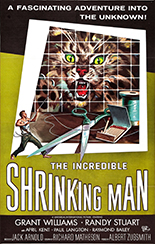

As I watched The Incredible Shrinking Man, I realized how many classic sci-fi movies I haven’t seen, creating a mental wish list that, ironically, doesn’t seem to be shrinking at all. At least I’m off to a good start, as the signifying combo of director Jack Arnold and writer Richard Matheson have crafted the perfect gateway to the outer limits of old-school speculative fiction.

As I watched The Incredible Shrinking Man, I realized how many classic sci-fi movies I haven’t seen, creating a mental wish list that, ironically, doesn’t seem to be shrinking at all. At least I’m off to a good start, as the signifying combo of director Jack Arnold and writer Richard Matheson have crafted the perfect gateway to the outer limits of old-school speculative fiction.

Based on the novel by screenwriter Matheson, everyman Scott (Grant Williams) is subjected to a mysterious cloud while boating with his wife one afternoon; maybe if he hadn’t been too lazy to get his own beer, he wouldn’t have been hit with this glittery dust. But he is, and within a couple of months, his clothes begin shrinking, creating adorable li’l khakis on him.

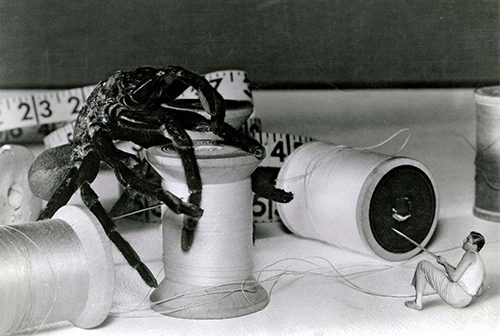

But his everyday wear is the least of his problems because, as he shrinks more and more, soon he’s living in a dollhouse and fighting a bastardly housecat in one of the most harrowing battles I’ve ever seen. Of course, I say that and, a few minutes later, he’s trapped in the basement fighting off a fucking spider with a sewing needle — yikes!

Complete with a truly metaphysical ending I think no one in their right mind was expecting — especially in 1957 — Arnold has crafted a thinking man’s science-fiction film that truly turns everyday household objects — and household creatures — into apocalyptic struggles of survival, ones that might prove a prick of irritancy to me but a visage of destruction to Scott.

And Pat Kramer, but at least she had that gorilla. —Louis Fowler