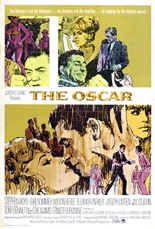

Frankie Fane loves the limelight. As played by Fantastic Voyage’s Stephen Boyd in a big, barking dog of a performance, Fane — a mere one letter from “fame,” folks! — is the (self-)center of his own universe at the Academy Awards, where he’s up for his first Oscar as Best Actor, against such stiff competition as Burt Lancaster and Richard Burton. How he got to that big night plays out in feature-length flashback in — what else? — The Oscar.

Frankie Fane loves the limelight. As played by Fantastic Voyage’s Stephen Boyd in a big, barking dog of a performance, Fane — a mere one letter from “fame,” folks! — is the (self-)center of his own universe at the Academy Awards, where he’s up for his first Oscar as Best Actor, against such stiff competition as Burt Lancaster and Richard Burton. How he got to that big night plays out in feature-length flashback in — what else? — The Oscar.

We watch as Frankie goes from two-bit traveling stripper spieler to accidental actor to hot new thing to box-office poison to (gasp!) pining for a TV pilot before a from-nowhere nomination saves his bacon. Along the way, he uses and abuses everyone in his immediate orbit: the talent scout who discovers him (Eleanor Parker, Eye of the Cat), his agent (comedian Milton Berle, playing it straight), his bump-and-grinder of a girlfriend (a super-sexy Jill St. John, Diamonds Are Forever), his eventual wife (Elke Sommer, The Wrecking Crew) and his best friend and manager, Hymie (crooner Tony Bennett, in his one and only film role not playing himself). Forget The Oscar; the marquee should have read The Asshole.

Thanks to the books The Golden Turkey Awards, The Official Razzie Movie Guide, Bad Movies We Love and their ilk, The Oscar has carried the burden as one of Hollywood’s legendary stinkers since its release, which isn’t playing fair. Oh, the melodrama is overwrought, all right, but I suspect its tarnished rep is more a case of Tinseltown not appreciating the suggestion that all is not golden in the moviemaking biz — especially one with such a nut-kick of an ending!

Thanks to the books The Golden Turkey Awards, The Official Razzie Movie Guide, Bad Movies We Love and their ilk, The Oscar has carried the burden as one of Hollywood’s legendary stinkers since its release, which isn’t playing fair. Oh, the melodrama is overwrought, all right, but I suspect its tarnished rep is more a case of Tinseltown not appreciating the suggestion that all is not golden in the moviemaking biz — especially one with such a nut-kick of an ending!

Immensely entertaining, The Oscar effectively killed the upwardly mobile careers of Boyd and director Russell Rouse, who co-wrote the screenplay with his regular collaborator Clarence Greene (Academy Award winners themselves for Pillow Talk) and some new kid named Harlan Ellison. What’s a revolutionary sci-fi author like him doing in a star-studded pic like this? While not entirely sure, I wonder if he is to blame for Frankie’s lingo-laden hepcat dialogue — to wit:

• “You fat honey-dripper!”

• “I’m up to here with all this bring-down!”

• “You’ve gotta be shuckin’ me!”

More narcissistic viewers might read this cautionary tale as more of an instruction manual, like Valley of the Dolls. While the two don’t reside on the same level of camp, make no mistake: They fucked. —Rod Lott