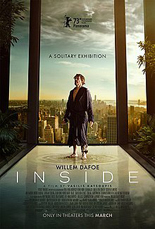

Writer-director Rose Glass’ previous film, Saint Maud, made waves among those who saw it, though it remains criminally underseen and underappreciated to this day. Fortunately, she has a new movie out, Love Lies Bleeding, featuring a more well-known cast and a more rounded advertising campaign, allowing (hopefully) more people to experience this filmmaker’s idiosyncratic visions of human interaction.

The film, co-written with Weronika Tofilska, stars Kristen Stewart as Lou, the manager of gym in 1980s New Mexico. There she meets Jackie (Katy O’Brian), a bodybuilder from a small town in Oklahoma, who is on her way to Las Vegas to compete in a bodybuilding tournament. The two hit it off immediately and begin a passionate relationship, with Lou not realizing Jackie had sex with her brother-in-law, J.J. (Dave Franco), the night she rolled into town — a tit-for-tat tryst Jackie only agreed to in order to get a job at the gun range J.J. works at.

The range happens to be owned by Lou’s father (Ed Harris, sporting a particularly hideous “skullet” — bald up top with long hair on the sides), a dangerous criminal who keeps various bugs and worms as pets. Lou doesn’t like Jackie working for her dad, with whom she has no more contact, but she’s forced into the same hospital room with him after J.J. beats Lou’s sister (Jena Malone) within an inch of her life. This act of domestic violence sets off a bloody chain reaction that puts both Lou and Jackie in danger, jeopardizing not just their lives but also their love for one another.

Steamy, funny, gory and ultimately weirder than you can imagine, Love Lies Bleeding feels like the unholy spawn of David Lynch, David Cronenberg and the early works of the Coen Brothers (particularly Blood Simple), but with a distinct queer-feminine perspective. Glass gloriously turns the neo-noir crime thriller on its head, much as she did with Saint Maud and the religious horror film, proving once again her prowess as a filmmaker and a unique cinematic voice. —Christopher Shultz