In 1982, nearly every kid with an Atari 2600 had one white-hot, new cartridge atop his or her Christmas or Hanukkah list: E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. By Dec. 26, I’m guessing they collectively experienced beggars’ remorse, because less than a year later, in September 1983, some 4 million units were dumped in the landfill of the small New Mexico town of Alamogordo.

In 1982, nearly every kid with an Atari 2600 had one white-hot, new cartridge atop his or her Christmas or Hanukkah list: E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. By Dec. 26, I’m guessing they collectively experienced beggars’ remorse, because less than a year later, in September 1983, some 4 million units were dumped in the landfill of the small New Mexico town of Alamogordo.

Or were they?

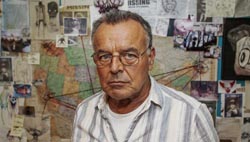

In the three decades since, the unceremonious mass burial of pop culture’s “worst video game of all time” has been shrouded in enough mystery to morph into urban legend. In the hour-and-some-change documentary Atari: Game Over, director Zak Penn — screenwriter of such Marvel movies as The Incredible Hulk, Elektra and X-Men: The Last Stand — literally goes digging for the truth.

In doing so, we get scoops of gossipy bits (and bytes) from Atari’s heyday in the early 1980s — a workplace of pot, booze, Jacuzzis and, every now and then, games that changed the world one rumpus room at a time. Their blocks-and-bricks graphics are laughable by today’s standards (although I still prefer them to modern games), but they were — and this is no overstatement — revolutionary.

In doing so, we get scoops of gossipy bits (and bytes) from Atari’s heyday in the early 1980s — a workplace of pot, booze, Jacuzzis and, every now and then, games that changed the world one rumpus room at a time. Their blocks-and-bricks graphics are laughable by today’s standards (although I still prefer them to modern games), but they were — and this is no overstatement — revolutionary.

One of those Atari 2600 programmers, Howard Warshaw, pushed the boundaries of game design further with such titles as Yars’ Revenge, Raiders of the Lost Ark and then the aforementioned E.T. Although ambitious in scope and intent, the cartridge proved a crushing disappointment with the public, thanks to a mix of corporate greed, Warshaw’s hubris and an impossibly compressed development schedule that made for maddening game play. What it did not do, contrary to public belief, is kill Atari.

With no shortage of self-deprecating humor, Penn’s Xbox-funded doc aims to rewrite passages of incorrect history and reverse the scorn that has hounded Warshaw ever since. In giving Warshaw a platform, Penn grants his film an emotional center as warm and winning as E.T.’s heartlight. Who would expect that watching grown men sift through trash could make for gripping viewing? That it does is but one reason Game Over simply cannot lose. —Rod Lott

Having paid homage to old-school slashers with the

Having paid homage to old-school slashers with the

Following the previous year’s

Following the previous year’s