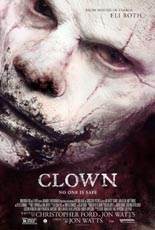

How strange that Clown began as a 78-second joke, as a fake trailer purporting to be the work of Hostel’s Eli Roth. How strange that the actual feature has Roth aboard as producer. What’s stranger than both those things is that there was enough in that concept worth expanding into a feature.

How strange that Clown began as a 78-second joke, as a fake trailer purporting to be the work of Hostel’s Eli Roth. How strange that the actual feature has Roth aboard as producer. What’s stranger than both those things is that there was enough in that concept worth expanding into a feature.

When the clown hired to enliven the birthday party for young Jack (Christian Distefano, Cut Bank) cancels during the event, it’s Dad to the rescue: Kent (Andy Powers, TV’s Taken miniseries), a real-estate agent, all too conveniently finds and dusts off a clown suit in the basement of a home he has on the market. Jack and friends are pleased, and one can tell in the eyes of Kent’s dental-hygienist wife, Meg (Laura Allen, TV’s The 4400), that her hubby is so totally getting laid tonight.

Or perhaps not. For some reason, the costume won’t come off! It resists scissors and serrated tools; the red, bulb nose is stuck to him like skin; the colorful curls of the wig have burrowed deep into his scalp; and that whiter shade of pale won’t wash off. And hell, what’s up with the rainbow-colored sputum? After medical treatment proves fruitless, Kent tracks down the former property owner (Peter Stormare, Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters), who offers three bits of worrisome news:

Or perhaps not. For some reason, the costume won’t come off! It resists scissors and serrated tools; the red, bulb nose is stuck to him like skin; the colorful curls of the wig have burrowed deep into his scalp; and that whiter shade of pale won’t wash off. And hell, what’s up with the rainbow-colored sputum? After medical treatment proves fruitless, Kent tracks down the former property owner (Peter Stormare, Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters), who offers three bits of worrisome news:

1. The clown of Nordic legend is not about twisting balloons into funny shapes.

2. It’s all about a demon bent on killing kids.

3. Kent’s turning into that.

Being presented without context — unlike, say, Roth’s Thanksgiving appetizer in Grindhouse — the fake Clown trailer of 2001 was difficult to peg as a pure put-on. At full-length, however, the intent of director Jon Watts (Cop Car) and co-writer Christopher Ford becomes Glass Plus-clear: scares above snorts. While the movie consistently works as a two-scoop cone of dark humor, its aim to disturb the viewer is primary; that it does so by putting kids in peril demonstrates that commitment, and Watts doesn’t use that lazily, like a short cut. Instead, aided by Powers and Allen’s real performances, he builds upon it, progressing with the aggression as poor Ken inversely descends from Dad jeans-wearing family man to hobo with trash bags duct-taped around his ankles to, ultimately, a face with a rictus carved in such a manner to haunt your dreams. —Rod Lott

At the tail end of the ’80s, what was in the Hollywood water supply that caused a wave of waterlogged movies? That pool included

At the tail end of the ’80s, what was in the Hollywood water supply that caused a wave of waterlogged movies? That pool included