Cameron Steele (Christopher George, Mortuary) is a famous escape artist who can get outta anything … but couldn’t get into a weekly time slot, unfortunately. From director John Llewellyn Moxey (Horror Hotel), the made-for-TV movie Escape may be a “failed” pilot for what should have been a series, but it is a damn fine hour and a half of, um, escapism.

Cameron Steele (Christopher George, Mortuary) is a famous escape artist who can get outta anything … but couldn’t get into a weekly time slot, unfortunately. From director John Llewellyn Moxey (Horror Hotel), the made-for-TV movie Escape may be a “failed” pilot for what should have been a series, but it is a damn fine hour and a half of, um, escapism.

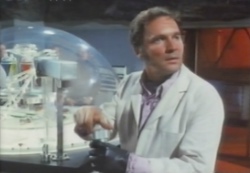

Now a private dick who lives above a bar catering to magicians, Steele takes a $25K gig to find Dr. Henry Walding (William Windom, She’s Having a Baby), a scientist who has gone missing — and whose lab has been torched — after cracking the code toward creation of a game-changing virus. As feared by Walding’s estranged daughter in the fashion industry (Marlyn Mason, Fifteen and Pregnant), the doc indeed has been kidnapped. As feared by no one, however, the culprit is Walding’s own brother, Charles (John Vernon, Killer Klowns from Outer Space), which is totally weird since he’s supposed to be deceased!

Charles is holding Henry captive, wishing to use his brother’s breakthrough for nefarious purposes. But the “why” is less important than the “where”: the Happyland amusement park! Yes, in order to spring Henry from captivity, Steele must navigate a funhouse laden with tricks and traps, which is where the telefilm lives up to the wonder promised by its way-out opening credits, scored by Mission: Impossible maestro Lalo Schifrin. In fact, Escape plays like an episode of M:I unfolding within a maze of mirrors — never a bad thing.

Charles is holding Henry captive, wishing to use his brother’s breakthrough for nefarious purposes. But the “why” is less important than the “where”: the Happyland amusement park! Yes, in order to spring Henry from captivity, Steele must navigate a funhouse laden with tricks and traps, which is where the telefilm lives up to the wonder promised by its way-out opening credits, scored by Mission: Impossible maestro Lalo Schifrin. In fact, Escape plays like an episode of M:I unfolding within a maze of mirrors — never a bad thing.

Serving up bonus kicks are members of the kitchen-sink supporting cast, including former Bowery Boy Huntz Hall, prime-past Oscar winner Gloria Grahame (The Bad and the Beautiful) and, as Steele’s associate, comedian Avery Schreiber (Loose Shoes) in a rare straight role — well, straight if we’re using his Doritos ads as the benchmark. —Rod Lott

Among all the

Among all the

Attention, cult cinemaniacs who like to sniff out zines catering to their peculiar tastes: Hunt down

Attention, cult cinemaniacs who like to sniff out zines catering to their peculiar tastes: Hunt down