As a religious-horror film, Immaculate earned my respect simply for leaning into internet commenter’s clutched-pearls cries of “evil” and “blasphemous” by using those nobodies’ quotes in its ad campaign, then doubling down with a one-day promotion for $6.66 admission. Members of the Neon marketing department, I proclaim you unholy geniuses.

Then, unlike most of the offended, I actually saw Immaculate. It retains my respect, so much so that I grant it a vow of obedience. (Poverty and celibacy, however? Let’s not go overboard.)

In Italy’s Our Lady of Sorrows, the newest nun is Cecilia (Sydney Sweeney, Madame Web), a young American woman. As Cecilia gets a tour of the 17th-century grounds and introduced to her fellow 21st-century sisters in Christ, the flick is so transparent in foreshadowing, it’s naked, e.g., “Be careful of this one. She bites.”

It’s not like things at the convent aren’t already, well, off; Cecilia’s spider-sense tingles from the outset. Then she gets pregnant, despite her iron-clad virginity. Holy calamity, scream insanity.

Some of Immaculate’s horrible happenings come as shocks, while others are so telegraphed, they’re practically stamped with the Western Union logo. And yet, even some of those shock, despite being expected. In the aforementioned tour, Cecilia’s ears perk up at a passing mention of “catacombs.” Ours do, too, knowing full well the story will near its end at this location. Sure enough, it does, but director Michael Mohan presents it like he’s leading viewers through a haunted house. It’s effective as, um, hell.

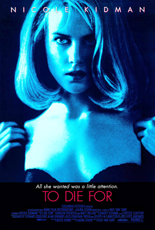

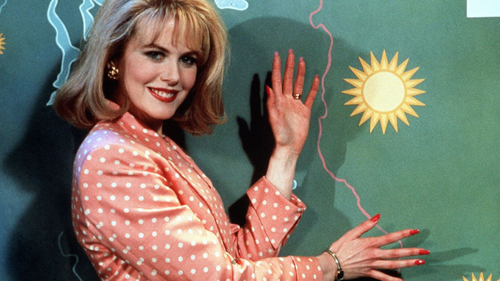

Sweeney, a shrewd businesswoman who also produced the film, seems uneasy in the first act. How much of that is her character’s nervousness, her performance limitations or my own inability to divorce my mind from her sexualized persona in past roles and public, I cannot determine. But once the shit hits the fan — or the God seed hits her womb, so to speak — Sweeney sizzles. Particularly excellent in the birthing scene, with the lens scrunched tight on her bloodied face for what seems like unbroken minutes, she’s a raw nerve.

Arguably the movies’ highest-profile example of the nunsploitation subgenre since Ken Russell danced with The Devils in 1971, Immaculate could have wussed out. It doesn’t. I admire its commitment to middle-brow nastiness and trashiness — and more so its refusal to back down, as Mohan (reuniting with Sweeney after their erotic thriller, The Voyeurs) and first-feature scribe Andrew Lobel carry their button-pushing transgression all the way through what its literally Immaculate’s final shot.

Be careful of this one. She bites. —Rod Lott