Which is harder to swallow: a dollhouse being haunted or a man moving his wife into a home she’s never seen? Either would be unthinkable, yet Amityville Dollhouse gives you both, God love it. (Look, after a lamp, a clock and a mirror, a dollhouse isn’t much of a stretch, but surprising your spouse with place of residence is step one to divorce court.)

Which is harder to swallow: a dollhouse being haunted or a man moving his wife into a home she’s never seen? Either would be unthinkable, yet Amityville Dollhouse gives you both, God love it. (Look, after a lamp, a clock and a mirror, a dollhouse isn’t much of a stretch, but surprising your spouse with place of residence is step one to divorce court.)

Capping off 10 months of he-man construction with his own bare hands, Bill Martin (Summer School nemesis Robin Thomas) has built a brand-new house for his new wife, Claire (Out of the Dark’s Starr Andreeff, whose name looks like the birth-certificate clerk had a stroke while typing), and their blended family of three kids. Inside the property’s original wooden shed, Bill finds a rather intricate dollhouse, which he gives to his daughter (Rachel Duncan, 1995’s Rumpelstiltskin) for her birthday. Because the toy is a to-scale replica of 112 Ocean Ave., Long Island, New York 11701, the Martin home quickly morphs into a metaphor for the dysfunctional American family, complete with a portal to hell via the den’s fireplace.

Yes, Amityville Dollhouse is a stupid title. Yes, Amityville Dollhouse has a stupid premise. No, Amityville Dollhouse is not boring.

Yes, Amityville Dollhouse is a stupid title. Yes, Amityville Dollhouse has a stupid premise. No, Amityville Dollhouse is not boring.

How could it be with a giant mouse under the girl’s bed? With zombie wasps that burrow into ears? With the head of doomed That ’70s Show starlet Lisa Robin Kelly bursting into flames? With Claire’s über-nerd son (Jarrett Lennon, Servants of Twilight) being terrified of spiders, but not the reanimated, guacamole-faced corpse behind his bedroom door? With Claire possessed into having MILFy fantasies about sex with her jock stepson (Allen Cutler, The Demon Within)?

The answer: It cannot and is not. I don’t know what Joshua Michael Stern (The Contractor) was thinking when he wrote the script, but I do know I’m glad director/producer Steve White doesn’t seem to have questioned it. Playing like Poltergeist by way of The Brady Bunch, this eighth film in the Amityville Horror franchise is indeed its looniest. —Rod Lott

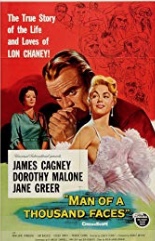

Who, we may ask, was Lon Chaney?

Who, we may ask, was Lon Chaney?