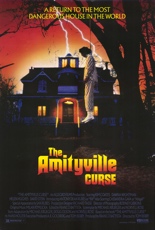

Hard to believe, but until the iPhone opened the floodgates for anyone to make a movie, we had the spread of Amityville Horror sequels pretty well contained. Of those pre-remake efforts, none is widely considered great, but none is worse than The Amityville Curse.

Hard to believe, but until the iPhone opened the floodgates for anyone to make a movie, we had the spread of Amityville Horror sequels pretty well contained. Of those pre-remake efforts, none is widely considered great, but none is worse than The Amityville Curse.

Made in Canada and supposedly based on Hans Holzer’s book of the same name, the fifth series entry has some set of balls in using a house that looks nothing — and I mean nothing — like the iconic, attic-as-eyes, real-life residence of 112 Ocean Avenue. It’s this film’s version of a soap opera’s cast switcheroo, but at least those shows pass it off as the result of plastic surgery. Curse has no excuse.

Married couple Deborah (Dawna Wightman, The Psycho She Met Online) and Marvin (David Stein, Hangfire) buy the abandoned abode as a fixer-upper. Being terrible hosts and even worse friends, they invite a few pals over to stay at the shithole, which has holes in the floor and rust in the pipes. To homeowners on a fixed income, those structural problems are frightening enough — and sadly more frightening than anything else Curse tosses our way: A barking dog! A hairy spider! A wine glass that breaks upon the clink of a toast! Another hairy spider! It’s enough to make Deb and her ESP exclaim, “There’s something evil in this house!”

Married couple Deborah (Dawna Wightman, The Psycho She Met Online) and Marvin (David Stein, Hangfire) buy the abandoned abode as a fixer-upper. Being terrible hosts and even worse friends, they invite a few pals over to stay at the shithole, which has holes in the floor and rust in the pipes. To homeowners on a fixed income, those structural problems are frightening enough — and sadly more frightening than anything else Curse tosses our way: A barking dog! A hairy spider! A wine glass that breaks upon the clink of a toast! Another hairy spider! It’s enough to make Deb and her ESP exclaim, “There’s something evil in this house!”

To be fair, yes, we’re shown supernatural elements as well, but if director Tom Berry (the Shelley Hack vehicle Blind Fear) can’t be bothered to be invested in them, why should we? More attention seems to be paid to the batty, cat-lady psychic with a glass eye (Helen Hughes, The Peanut Butter Solution). Points to Wightman for enacting the hardware-store defense strategy nearly a quarter-century before Denzel Washington made it famous, but too little, too late: The Amityville Curse is one mundane movie. It might work rebooted as a “reality” series for HGTV. —Rod Lott

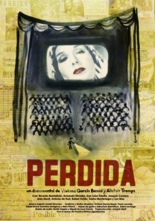

As a boy, I would’ve loved to have grown up in a family of naked women, robot monsters, Aztec mummies and masked wrestlers. But I’m not Viviana García-Besné.

As a boy, I would’ve loved to have grown up in a family of naked women, robot monsters, Aztec mummies and masked wrestlers. But I’m not Viviana García-Besné. Through interviews with surviving family members of the Calderón film dynasty, she attempts to ferret fact from fiction; dusty home movies and handwritten letters help fill in the gaps, as does a third-act raid of a film vault.

Through interviews with surviving family members of the Calderón film dynasty, she attempts to ferret fact from fiction; dusty home movies and handwritten letters help fill in the gaps, as does a third-act raid of a film vault. The brothers’ crooked, oft-controversial path is paved with acts of monopoly, infidelity and forgery, involving personalities like the revolutionary Pancho Villa, actress Lupe Vélez, mambo king Perez Prado,

The brothers’ crooked, oft-controversial path is paved with acts of monopoly, infidelity and forgery, involving personalities like the revolutionary Pancho Villa, actress Lupe Vélez, mambo king Perez Prado,