In the year 2020, America has become the first chapter of a particularly bad dystopian sci-fi novel. That’s probably why the excessively optimistic Bill & Ted Face the Music might be the most needed movie of the year, giving a bit of cinematic hope in our hour of needful reality.

In the year 2020, America has become the first chapter of a particularly bad dystopian sci-fi novel. That’s probably why the excessively optimistic Bill & Ted Face the Music might be the most needed movie of the year, giving a bit of cinematic hope in our hour of needful reality.

Like any self-respecting member of Generation X, 1989’s Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (and, to a lesser extent, 1991’s Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey) was a defining moment for me and most of my friends, waiting desperately for the fictitious day that the music of Wyld Stallyns changes the world as we know it forever.

Of course, it never happened.

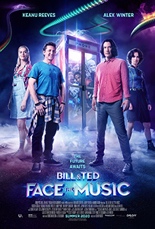

Now middle-aged and married with daughters, Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves) are still trying to write the song that will evolve humanity toward a peaceful existence, with no luck. Ironically, time has seemingly ran out and the fabric of reality is about to collapse in on itself unless the mythical track is finally completed in about 70 minutes. This gives the guys the bright idea to time-travel to the future and steal the song from themselves.

Now middle-aged and married with daughters, Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves) are still trying to write the song that will evolve humanity toward a peaceful existence, with no luck. Ironically, time has seemingly ran out and the fabric of reality is about to collapse in on itself unless the mythical track is finally completed in about 70 minutes. This gives the guys the bright idea to time-travel to the future and steal the song from themselves.

While that’s going on, daughters Billie (Brigette Lundy-Paine) and Thea (Samara Weaving) use a spare time machine to go backward and create the greatest band ever, collecting musical icons such as Louis Armstrong, Jimi Hendrix, Mozart and so on. It’s not a spoiler if I say they definitely have the more solid plan.

With the return of Death (William Sadler), a holographic Rufus (George Carlin) and the never-was catchphrase “Station!,” as much as a goofy trip down memory lane as it wants to be (and is), it becomes something more in our current climate, with Reeves and Winter portraying two genuinely good guys compelled to do the right thing, even if it means giving the role of planetary saviors to their daughters.

With the return of Death (William Sadler), a holographic Rufus (George Carlin) and the never-was catchphrase “Station!,” as much as a goofy trip down memory lane as it wants to be (and is), it becomes something more in our current climate, with Reeves and Winter portraying two genuinely good guys compelled to do the right thing, even if it means giving the role of planetary saviors to their daughters.

It’s hard to not sound apocalyptic when recommending Bill & Ted Face the Music, but it is the movie we truly need right now — and maybe that’s the true peace-bringing message of the Wyld Stallyns and their excellent adventures. —Louis Fowler