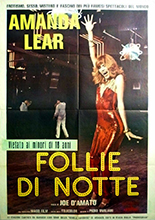

Before Rinse Dream turned the sex club in an atomic nightmare, director Willy Roe — with skin queen Mary Millington in her last film — turned it into a kitschy daydream, erections not included.

Before Rinse Dream turned the sex club in an atomic nightmare, director Willy Roe — with skin queen Mary Millington in her last film — turned it into a kitschy daydream, erections not included.

In London’s lily-white Blues Club — apparently the top spot for the hair-filled nudity in Mayfair — the so-called queen of the joint, literally and figuratively, is Millington, who writhes around on stage, moving her pubic mound up and down for all the patrons seemingly live there to see. In between, the rampant backstage cattiness of nude infighting truly makes Queen of the Blues a film to watch.

The main plot, if you can call it that, is about gangsters demanding protection money from the owner, although it’s probably around five minutes of actual film, as so much of this is dedicated to the sexy strippers, with a preamble by a terrible comedian who tempts me to push the fast-forward button.

A just a little over an hour — a mercifully short running time I definitely miss in film — Mary and her stripper friends soon attempt revenge on the gangsters. The sad thing is that Millington, by then the prime porn star of England, looks tired and, soon enough, would be found dead. Her publisher, however, was able to farm her buxom body into two more features, both of which are terrible.

Also, in case you’re wondering, there is no actual blues music to be heard here, but plenty of horrific dance tunes. I guess Queen of the Disco wouldn’t work, though. —Louis Fowler

In indie horror’s digital DIY era of today, everyone who wants to make a horror movie can and does. This floods the market with dreck — and because even dreck has a minute’s worth of good parts to craft an appealing-enough trailer and inspire an eyeball-grabbing cover — the market is rewarded with rental dollars from viewers left wanting. They’re Outside offers the opposite experience: File the trailer and poster art under “no great shakes,” but the movie itself is that increasingly elusive, rough-’round-the-edges gem.

In indie horror’s digital DIY era of today, everyone who wants to make a horror movie can and does. This floods the market with dreck — and because even dreck has a minute’s worth of good parts to craft an appealing-enough trailer and inspire an eyeball-grabbing cover — the market is rewarded with rental dollars from viewers left wanting. They’re Outside offers the opposite experience: File the trailer and poster art under “no great shakes,” but the movie itself is that increasingly elusive, rough-’round-the-edges gem.