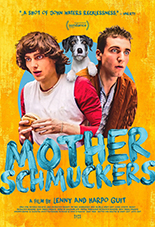

Abandon hope, all ye who enter Mother Schmuckers, Belgium’s answer to Dumb and Dumber. The leads, played by filmmaking brothers Lenny and Harpo Guit, are even the human equivalent of Lloyd Christmas’ “most annoying sound in the world.”

Abandon hope, all ye who enter Mother Schmuckers, Belgium’s answer to Dumb and Dumber. The leads, played by filmmaking brothers Lenny and Harpo Guit, are even the human equivalent of Lloyd Christmas’ “most annoying sound in the world.”

As perpetually hungry, poverty-stricken brothers Issachar (who looks like Emo Philips had sex with Elijah Wood) and Zabulon (who doesn’t), the Guits lose their mother’s beloved dog, January Jack. That’s it for a story; the boys just run around town, finding shenanigans at every turn: playing with a loaded gun, eating a maggot-ridden burger, dancing in a music video. In the highlight, as it were,

Issachar uses unconvincing carpet scraps to pass for a dog to gain access into a club — uh-oh, it’s a bestiality club, yuk yuk!

Mother Schmuckers shows its stripes in the opening scene, where Issachar and Zabulon cook poop. When executed well, gross-out comedy can garner laughs so large, they strain your stomach muscles. That’s not the case here; the Guits present the situation without real jokes attached. This is not a case of European humor failing to translate to this stupid American’s brain or offending my delicate sensibilities, as Denmark’s Klown is as riotous as they come, and France’s recent Mandibles is full of laugh-aloud moments, too.

By contrast, Mother Schmuckers simply is not funny because the Guits don’t push the bits beyond merely presenting them, and that’s not enough. I laughed exactly once, at someone’s apt summation of Issachar: “He looks like a Playmobil.” At least the movie is pretty much over with after 65 minutes — a tiresome stretch in any language for gags this flat and contemptible. Comparisons to John Waters are unfair to John Waters. —Rod Lott

I love a good heist movie. Thirty Dangerous Seconds is not one.

I love a good heist movie. Thirty Dangerous Seconds is not one.