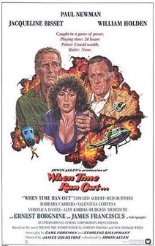

When Time Ran Out … could refer to the end of producer Irwin Allen’s reign as the movies’ “master of disaster.” A huge financial bomb, the film forced him into made–for–TV movie pastures for the half-dozen years his once-golden career had left. It represents something of an Irwin Allen all-star edition, too, reuniting The Towering Inferno above-the-line talent Paul Newman and William Holden, as well as The Poseidon Adventure second fiddles Ernest Borgnine and Red Buttons. Too bad getting the gang back together was all for naught.

When Time Ran Out … could refer to the end of producer Irwin Allen’s reign as the movies’ “master of disaster.” A huge financial bomb, the film forced him into made–for–TV movie pastures for the half-dozen years his once-golden career had left. It represents something of an Irwin Allen all-star edition, too, reuniting The Towering Inferno above-the-line talent Paul Newman and William Holden, as well as The Poseidon Adventure second fiddles Ernest Borgnine and Red Buttons. Too bad getting the gang back together was all for naught.

You can break the story down to four primary beats:

• On a South Pacific island, an oil drilling foreman named Hank (Newman) is deeply concerned by a nearby active volcano.

• Shelby (Holden), a money-first hotel developer, not so much.

• Everyone is screwing around on one another, making for a cast list bordering on the incestuous.

• The volcano erupts.

In the compulsory hullabaloo, Hank and his tight-shirted ex-girlfriend/Shelby’s current girlfriend (Jacqueline Bisset, The Deep) rally people to trek to safety — or die trying. Minorities fare poorly, in part because they’re not white enough to hold on tight, I guess. The big set piece is rather dull, unless watching Burgess Meredith (SST: Death Flight) doing a wire-walking act across a rickety bridge in real time is your idea of crackling entertainment. James Goldstone, who directed the infinitely superior Rollercoaster, pulls off a flood sequence that is better than any of the lava scenes, because those look like you’re peering down into a can of red paint being mixed at Home Depot. The climactic hotel destruction should be the pièce de résistance; instead, it’s so cartoony, today’s viewer would not flinch if the word “KABLOOEY!” appeared onscreen.

In the compulsory hullabaloo, Hank and his tight-shirted ex-girlfriend/Shelby’s current girlfriend (Jacqueline Bisset, The Deep) rally people to trek to safety — or die trying. Minorities fare poorly, in part because they’re not white enough to hold on tight, I guess. The big set piece is rather dull, unless watching Burgess Meredith (SST: Death Flight) doing a wire-walking act across a rickety bridge in real time is your idea of crackling entertainment. James Goldstone, who directed the infinitely superior Rollercoaster, pulls off a flood sequence that is better than any of the lava scenes, because those look like you’re peering down into a can of red paint being mixed at Home Depot. The climactic hotel destruction should be the pièce de résistance; instead, it’s so cartoony, today’s viewer would not flinch if the word “KABLOOEY!” appeared onscreen.

Early in the movie is a tantalizing bit of would-be foreshadowing as Veronica Hamel (Beyond the Poseidon Adventure) warns of footlong centipedes emerging from the volcano … yet we never get to see them. In their place are James Franciscus (Beneath the Planet of the Apes) in a uniform made of Jiffy Pop foil; Edward Albert (The House Where Evil Dwells) sporting a ’do seemingly shaped by a cafeteria lady’s hairnet; Pat Morita (Do or Die) doing what amounts to an impression of Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s; and Allen’s untalented wife, Sheila, in a most unflattering muumuu. —Rod Lott