For a made-for-TV movie, Superdome sure is rife with vice: Sex! Drugs! Violence! Dick Butkus!

For a made-for-TV movie, Superdome sure is rife with vice: Sex! Drugs! Violence! Dick Butkus!

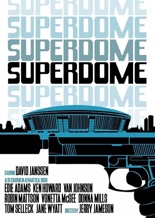

And all that takes place within the five days the fictional Cougars have come to New Orleans to play the Super Bowl, meaning team manager Mike Shelley (David Janssen, Mayday at 40,000 Feet!) has a lot on his hands, including a comely reporter (Donna Mills, Hanging by a Thread) who’s not above sex with seniors to extract quotes — or, for that matter, a plate of fried catfish.

Thrown into the suds of Superdome are a marriage on the brink, a potentially exiting star quarterback (Tom Selleck, Runaway), an illegal gambling plot with mob muscle and, above all, murder! Someone is shooting team staff members to death, with poisoned ginger ale and electrocution by whirlpool also on tap for attempts. Curiously, there is next to no football.

In charge of this whole mess is director Jerry Jameson, fresh from Airport ’77 and likely hired for his ability to corral an all-star cast; here, that includes such screen sirens as Edie Adams, Vonetta McGee, Jane Wyman and Bubba Smith.

In charge of this whole mess is director Jerry Jameson, fresh from Airport ’77 and likely hired for his ability to corral an all-star cast; here, that includes such screen sirens as Edie Adams, Vonetta McGee, Jane Wyman and Bubba Smith.

For all Jameson’s skill at actor control, he is unable to wring any suspense from the stew. Had the script stuck to the killer angle and run with it, he might have something, like the then-2-year-old stadium-sniper thriller Two-Minute Warning. Instead, just as we’re shown a pair of black gloves pulling the trigger, Superdome pivots to a storyline of dramatically lower stakes, like Ken Howard’s aching knee. Fumble! —Rod Lott