Oh, I assume World Trade Organization execs may hate it, but I find it difficult to believe that most people who can think for themselves would fail to get — at the very least — a chuckle out of The Yes Men, a documentary about a pair of political pranksters. Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno comprise the titular twosome, who use a grant from musician Herb Alpert to help them travel the globe to speak about anti-globalization in the most outlandish ways.

Oh, I assume World Trade Organization execs may hate it, but I find it difficult to believe that most people who can think for themselves would fail to get — at the very least — a chuckle out of The Yes Men, a documentary about a pair of political pranksters. Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno comprise the titular twosome, who use a grant from musician Herb Alpert to help them travel the globe to speak about anti-globalization in the most outlandish ways.

It all begins when visitors to their WTO parody website don’t even read the print — fine or otherwise — and extend invitations to lectures at international conferences as WTO reps. The Yes Men are all too eager to accept, and the film follows them hatching their (mostly) harmless plots and executing them in public.

This includes demonstrating a prototype of the “future leisure suit,” which contains an inflatable, phallic appendage containing a screen on which corporate heads can monitor their workforce remotely. This outfit and accompanying suggestion that slavery was a good thing aren’t questioned by anyone. At least a classroom of collegians is sharp enough to turn on a supposed WTO/McDonald’s partnership presentation in which Americans’ feces would be piped to Third World countries and recycled into “reBurgers.”

This includes demonstrating a prototype of the “future leisure suit,” which contains an inflatable, phallic appendage containing a screen on which corporate heads can monitor their workforce remotely. This outfit and accompanying suggestion that slavery was a good thing aren’t questioned by anyone. At least a classroom of collegians is sharp enough to turn on a supposed WTO/McDonald’s partnership presentation in which Americans’ feces would be piped to Third World countries and recycled into “reBurgers.”

My only complaint about The Yes Men is that 83 minutes just wasn’t enough to satisfy me. I laughed out loud too many times to allow the culture-jamming fun to end so soon. It’s directed by the geniuses behind American Movie, perhaps the greatest documentary ever made, so you know you’re in good hands with this one. —Rod Lott

Speaking of poop, Treadwell is shown touching a fresh, steaming pile because he thinks it’s beautiful it came from the butt of his beloved Wendy. If you think that’s weird, wait until he sheds tears over a dead bee. Yes, there’s something that wasn’t right with the man; apparently, he drank too many brain cells away to think he had forged some relationship with them that they understood his words. He’s like

Speaking of poop, Treadwell is shown touching a fresh, steaming pile because he thinks it’s beautiful it came from the butt of his beloved Wendy. If you think that’s weird, wait until he sheds tears over a dead bee. Yes, there’s something that wasn’t right with the man; apparently, he drank too many brain cells away to think he had forged some relationship with them that they understood his words. He’s like

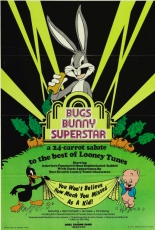

It’s this material, most of which is spoken by one of Bugs’ papas, Bob Clampett, that generated some hurt feelings when this film was released. Co-creators Avery and Friz Freleng are also interviewed, and while Clampett had complimentary things to say about Chuck Jones, Jones — who could nurse a grudge like Silas Marner could nurse a nickel — accused Clampett of being a credit hog. The thing is, when this picture was made, almost everyone from the days of classic animation was looking for credit for the work he’d done for hire in the 1930s-1950s, so a lot of exaggeration was going around.

It’s this material, most of which is spoken by one of Bugs’ papas, Bob Clampett, that generated some hurt feelings when this film was released. Co-creators Avery and Friz Freleng are also interviewed, and while Clampett had complimentary things to say about Chuck Jones, Jones — who could nurse a grudge like Silas Marner could nurse a nickel — accused Clampett of being a credit hog. The thing is, when this picture was made, almost everyone from the days of classic animation was looking for credit for the work he’d done for hire in the 1930s-1950s, so a lot of exaggeration was going around.

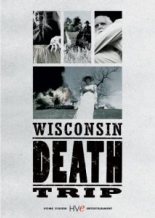

Many of the film’s visuals are derived from period photos taken by Charles Van Schaik, including a lot of children in their coffins, and the narration by Ian Holm comes entirely from newspaper articles and obituaries of the time. Many of the incidents are re-created using actors.

Many of the film’s visuals are derived from period photos taken by Charles Van Schaik, including a lot of children in their coffins, and the narration by Ian Holm comes entirely from newspaper articles and obituaries of the time. Many of the incidents are re-created using actors.