I completely understand why a chunk of cult-film fandom loathes Mystery Science Theater 3000; to paraphrase singer and arrest magnet Bobby Brown, that’s their prerogative. Speaking for myself, however, I wouldn’t be here — as in, this site — without it, as the TV show introduced me to a netherworld of movies I was unaware of, and pushed me to discover more. (You can read more about that in the introduction to my book, Flick Attack Movie Arsenal.)

I completely understand why a chunk of cult-film fandom loathes Mystery Science Theater 3000; to paraphrase singer and arrest magnet Bobby Brown, that’s their prerogative. Speaking for myself, however, I wouldn’t be here — as in, this site — without it, as the TV show introduced me to a netherworld of movies I was unaware of, and pushed me to discover more. (You can read more about that in the introduction to my book, Flick Attack Movie Arsenal.)

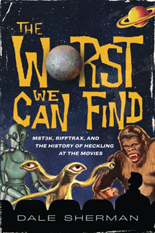

Needless to say, you know right away whether Dale Sherman’s The Worst We Can Find: MST3K, Rifftrax, and the History of Heckling at the Movies is for you. The paperback is new from Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, his frequent publisher (Armageddon Films FAQ, Quentin Tarantino FAQ, et al.).

Despite the subtitle, this is the history of Joel Hodgson’s long-running Peabody Award-winning series first and foremost, with everything else adjacent or tangential. In fact, skip the first chapter on the origins of heckling (if the phrase “According to Merriam-Webster” doesn’t make you do so already) and get right into the goods with a look at MST3K precursors, from Woody Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily? to the syndicated TV show Mad Movies with the L.A. Connection. (Speaking of, Mike White’s 2014 book of the same name covers even more forerunners.)

From there, Sherman paints a full picture of the series’ evolution from local UHF sensation in Minneapolis to the national stage, where it was juggled among a couple of channels, revived for streaming and resurrected yet again for its current, crowdfunded home on the internet. You may know all of that already, but Sherman fills in the details of the writing process, the constant budget constraints, how films were selected, which ones they admit didn’t work, why each cast member left, the in-fighting behind the scenes, the battles with Hollywood to make Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie and all the members’ side projects, riff-related or otherwise (mostly the former).

Even if Sherman didn’t conduct the interviews that revealed these details, he certainly did his homework. The Worst We Can Find gives a thorough overview of the series, breezing by at a level firmly between a cursory flyover and a nails-dirty dig into the weeds. Really, going straight down the middle is the right call: It’s accessible without lacking substance, and comprehensive without veering into the arcane or anal-retentive. So what if the author’s lightly peppered stabs at humor fizz like a day-old Dr Pepper? He’s writing about a show he loves so much, it’s natural Sherman get caught in the enthusiasm. If his passion hadn’t come through is when we would worry. —Rod Lott