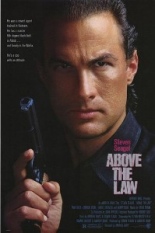

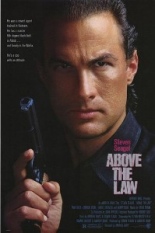

It’s hard to remember a time when Steven Seagal was actually cool. It was 1988, when nobody knew who he was, yet here he was, headlining a pretty good B-actioner called Above the Law. It heralded the dawn of a new (stoic) action star, whose career would be packed with hit after hit … until it imploded.

It’s hard to remember a time when Steven Seagal was actually cool. It was 1988, when nobody knew who he was, yet here he was, headlining a pretty good B-actioner called Above the Law. It heralded the dawn of a new (stoic) action star, whose career would be packed with hit after hit … until it imploded.

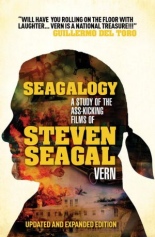

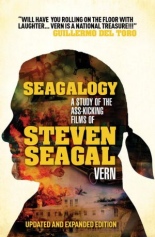

Each and every step is chronicled, examined, poked and prodded by single-monikered Internet movie reviewer Vern in the exhaustive and exhaustingly hilarious Seagalogy: A Study of the Ass-Kicking Films of Steven Seagal, now in a bigger, funnier, ass-kickier updated edition from its original 2008 release.

Vern begins exactly where he should, with a dissection of Above the Law that runs a staggering 16 pages. His love for the movie is evident, but that doesn’t mean he’s not above taking some potshots (“It’s obvious that the CIA is corrupt is they’re gonna hire a guy who looks like Henry Silva. I mean look at the guy’s face. Don’t tell me they didn’t know that motherfucker was evil”).

Seagal’s debut marks the start of what Vern terms his “Golden Era.” (For the record, the book is divided into that, plus the “Silver Era,” “Transitional Period,” “DTV Era” and the all-new, 10-chapter “Chief Seagal Era,” from 2009 to the present). Squee over Machete as much as you want, but all Seagal fans know that the early days were the best, given the too-much-fun, mega-violent, ponytail-laden shoot-’em-up romps that were Hard to Kill, Marked for Death and Out for Justice.

Seagal’s debut marks the start of what Vern terms his “Golden Era.” (For the record, the book is divided into that, plus the “Silver Era,” “Transitional Period,” “DTV Era” and the all-new, 10-chapter “Chief Seagal Era,” from 2009 to the present). Squee over Machete as much as you want, but all Seagal fans know that the early days were the best, given the too-much-fun, mega-violent, ponytail-laden shoot-’em-up romps that were Hard to Kill, Marked for Death and Out for Justice.

Next came Seagal’s biggest critical and commercial hit, Under Siege, which heralded the beginning of the “Silver Era,” a time when the actor’s clout grew to such that he began exerting more of his influence into his films, like the environmental speech to the audience that closed On Deadly Ground, also his directorial debut. It was a period that also saw his first sequel (Under Siege 2), his first death (a fraction into the incredibly underrated Executive Decision) and an attempt at gloomy serial killer/buddy cop films (The Glimmer Man).

Of that last one — a big ol’ failure at the box office — Vern wonders about the reasoning behind Seagal’s character’s nickname of “The Glimmer Man” because when he served as an assassin, a glimmer of light would be the last thing his targets would see before death: “You can’t just assume they saw a glimmer unless there is some kind of evidence. Unless somebody carved ‘glimmer’ into the jungle floor with a twig as they gasped their last breath, this glimmer man story just does not hold water.”

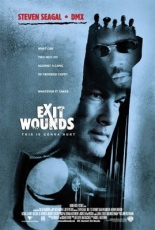

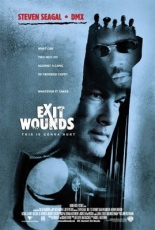

Seagal’s “Transitional Period” includes his first two straight-to-video movies and two attempts at a box-office comeback, one of which worked: Exit Wounds. But Half Past Dead did not, and that gave way to the “DTV Era,” where he apparently has resigned to play for the rest of his natural born life. (Even the long-delayed anthology comedy The Onion Movie, in which Seagal spoofs himself in a fake movie trailer for Cockpuncher, deservedly skipped the multiplex for shiny discs.)

Seagal’s “Transitional Period” includes his first two straight-to-video movies and two attempts at a box-office comeback, one of which worked: Exit Wounds. But Half Past Dead did not, and that gave way to the “DTV Era,” where he apparently has resigned to play for the rest of his natural born life. (Even the long-delayed anthology comedy The Onion Movie, in which Seagal spoofs himself in a fake movie trailer for Cockpuncher, deservedly skipped the multiplex for shiny discs.)

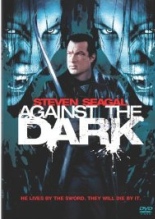

I knew Seagal had made a lot of low-budget flicks that bypassed theaters to premiere on DVD. Heck, I had seen exactly two of them: Ticker, which isn’t overtly terrible, and Submerged, which is. (I recently tried to watch Against the Dark, the 2009 one pitting him against vampires, but was so bored that I gave up about 15 minutes in.) But did you know that he’s made — at press time — more than two dozen of these things? All of them have appeared within the last decade. Compare that number to his theatrical output: 13. That’s sad.

These DTV efforts sport terribly generic titles (Black Dawn, Urban Justice) that render them interchangeable. And that’s the only downside to Seagalogy: Because the films themselves are so repetitive, so be it the book. It may be different for those who’ve actually seen these movies, but the wide majority of us have not, and you can only read “ex-CIA” so often before your eyes gloss over. Still, Vern’s descriptions remain uproarious, and likely more entertaining than the flicks.

These DTV efforts sport terribly generic titles (Black Dawn, Urban Justice) that render them interchangeable. And that’s the only downside to Seagalogy: Because the films themselves are so repetitive, so be it the book. It may be different for those who’ve actually seen these movies, but the wide majority of us have not, and you can only read “ex-CIA” so often before your eyes gloss over. Still, Vern’s descriptions remain uproarious, and likely more entertaining than the flicks.

Take, for example, the 9/11-informed Born to Raise Hell, among the new entries: “[Seagal] shoots 14 holes through the wall around a door and kicks it out like a perforated coupon. I hope that’s a real police technique.” Or his short-lived reality TV series, Lawman, also fresh to this edition: “In movies Seagal interrupts major crimes in progress. He happens to run into armed robbers while going to the liquor store, or he’s there to save the day when the Vice President is attacked. But in real life Seagal has to drive around all night staring at people on the streets just to find an open container or a shitty driver who turns out to have outstanding warrants.”

This Vern fellow doesn’t put out books fast enough. His 2010 Seagalogy follow-up, Yippee Ki-Yay Moviegoer!, is awesome, but that was two years ago now. He also pens a column in CLiNT, Mark Millar’s UK comics magazine, but nine pages in one year is like nothing. I want more! More! More! Would it kill him to produce the definitive work on all the movies made by all of The Expendables? I think not.

It is interesting that twice now, Vern writes, two of these DTV-era Seagal pictures were shot as Alien-esque sci-fi invasions — Submerged and Attack Force — only to be shorn of those elements entirely in the editing room. Now that’s moviemaking! It also says a lot about the quality and care put into these flicks when, as Vern points out, one of them — Flight of Fury — was actually a remake of a Michael Dudikoff movie … and Seagal didn’t even know it! (Notes Vern, “Both versions have topless women in them,” so whew!)

It is interesting that twice now, Vern writes, two of these DTV-era Seagal pictures were shot as Alien-esque sci-fi invasions — Submerged and Attack Force — only to be shorn of those elements entirely in the editing room. Now that’s moviemaking! It also says a lot about the quality and care put into these flicks when, as Vern points out, one of them — Flight of Fury — was actually a remake of a Michael Dudikoff movie … and Seagal didn’t even know it! (Notes Vern, “Both versions have topless women in them,” so whew!)

In a stroke of semi-genius, Vern also reviews Seagal’s two CDs, a 2006 live concert in Seattle of The Steven Seagal Blues Band, and the man’s branded Lightning Bolt Energy Drink, which remains, to this day, the worst thing that’s ever been in my mouth.

Vern likes the beverage, but I won’t hold that against him. I also won’t hold his association with Ain’t It Cool News against him, because — unlike that site’s “pwesent”-begging, self-aggrandizing, spelling-and-grammar-challenged but well-connected leader, Vern can actually write. And Seagalogy not only made me laugh my ass off, but sent me to Amazon to buy some of the early Seagal DVDs I didn’t already own.

I said it before, and I’ll say it again: This book is an instant cult classic. Now for the second time in a row. —Rod Lott

Buy it at Amazon.

Asks venerated critic David Denby in the ’78 Superman-styled title of his new book, Do the Movies Have a Future? (Spoiler alert: Yes. Yes, they certainly do.)

Asks venerated critic David Denby in the ’78 Superman-styled title of his new book, Do the Movies Have a Future? (Spoiler alert: Yes. Yes, they certainly do.)

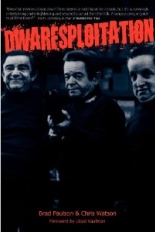

You’re not going to get deep insight into the films featured. That’s not the point. The point is celebrating the little guy, in an easygoing manner that’s both affectionate and amusing. For example, take this sentence from their look at

You’re not going to get deep insight into the films featured. That’s not the point. The point is celebrating the little guy, in an easygoing manner that’s both affectionate and amusing. For example, take this sentence from their look at