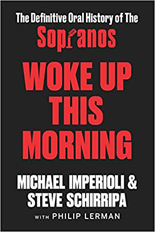

Sopranos castmates Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Baccalieri) host the popular podcast Talking Sopranos. The results of their numerous interviews with the HBO show’s cast and crew are collected in Woke Up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of The Sopranos. It is an informative and revealing look at the creation and production of the innovative and enduring cable TV series.

Sopranos castmates Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Baccalieri) host the popular podcast Talking Sopranos. The results of their numerous interviews with the HBO show’s cast and crew are collected in Woke Up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of The Sopranos. It is an informative and revealing look at the creation and production of the innovative and enduring cable TV series.

Many of the revelations are humorous. For example, Lorraine Bracco (psychiatrist Dr. Melfi) tells what the late James Gandolfini (mobster Tony Soprano) would do to distract her during their scenes in the therapy office. Or why Jamie-Lynn Sigler thought she had to sing during her audition for the role of Tony’s daughter, Meadow Soprano.

Others are more somber, such as series creator David Chase describing what it felt like to tell a performer their character was being killed off. Many of those performers also share their reactions when informed their parts were being whacked.

The structure generally follows the six seasons. The authors often alert readers to the cast or crewmember being interviewed, and the subject they discuss. Technical terms are defined for the benefit of the reader. One chapter is devoted entirely to the writers’ room and details how stories and scripts were developed. It ends with Schirripa’s top 10 best Sopranos quotes. A later chapter discusses how pop music was used to enhance episodes. A photo section near the middle features photos on the set or at various production-related events.

Throughout, Imperioli, Schirripa and those interviewed stress how the cable series stretched the boundaries of television. The effort was always to make scenes more cinematic, and the characters more diverse than usual. Readers will discover things they neither knew nor noticed during their initial viewing.

Woke Up This Morning comes highly recommended — and essential reading for all Sopranos fans. You’ll soon find yourself streaming specific episodes to take advantage of the authors’ insights. —Alan Cranis