The Haunting of Hill House (2018) vs. The Ghosts of Monday (2022)

The Haunting of Hill House (2018) vs. The Ghosts of Monday (2022)

1. Paul McCartney, “Spies Like Us”

2. Paul Simon, “You Can Call Me Al”

3. Ray Parker Jr., “Ghostbusters”

—Rod Lott

Aside from being a winking pun, The Joy of Sets hasn’t been named willy-nilly. Lee Goldberg’s collection of 11 preview articles, mostly for Starlog, indeed captures the feeling of reading about hotly anticipated movies in the blockbuster excess of the ’80s. One can sense the then-young film obsessive had to have felt with such access to the making of multimillion-dollar pictures. Some of his subjects exhibited joy, too.

Aside from being a winking pun, The Joy of Sets hasn’t been named willy-nilly. Lee Goldberg’s collection of 11 preview articles, mostly for Starlog, indeed captures the feeling of reading about hotly anticipated movies in the blockbuster excess of the ’80s. One can sense the then-young film obsessive had to have felt with such access to the making of multimillion-dollar pictures. Some of his subjects exhibited joy, too.

Take John Drimmer, first-time scripter of 1984’s Iceman, who can hardly believe his luck. Watching the daily rushes “drives me wild. It’s just wonderful,” he told Goldberg. “I mean, here I am, sitting there, drinking beers and watching them create this make-believe world of mine.”

While not all of these Interviews on the Sets of 1980s Genre Movies (as the subtitle has it) entail movies worth watching, Goldberg’s reports never fail to entertain. As with his recent James Bond Films volume, one reason is revisiting a once-dominant type of film journalism; the larger is the in-hindsight delight of checking how forecasts panned out.

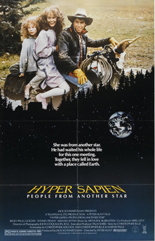

After all, you remember that beloved classic of 1986, Hyper Sapien: People from Another Star. No? Are you telling me producer Jack Schwartzman’s prediction regarding his E.T. rip-off didn’t come true? For the record, his quote to Goldberg: “If Keenan Wynn doesn’t wind up with the Academy Award nomination for Hyper Sapien, I’ll eat it.” (Nom-nom-nom, Jack.)

After all, you remember that beloved classic of 1986, Hyper Sapien: People from Another Star. No? Are you telling me producer Jack Schwartzman’s prediction regarding his E.T. rip-off didn’t come true? For the record, his quote to Goldberg: “If Keenan Wynn doesn’t wind up with the Academy Award nomination for Hyper Sapien, I’ll eat it.” (Nom-nom-nom, Jack.)

Horror icon Wes Craven fares far better, saying of A Nightmare on Elm Street, “I really feel this will be landmark film for me, my watershed film.” Dead on! More amazing is how forthcoming the Back to the Future crew is about scrubbing all the Eric Stoltz footage and starting anew. Would Robert Zemeckis do the same today? (No.)

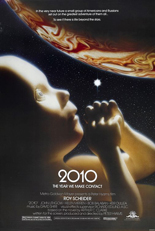

For me, the most interesting account of the bunch belongs to Peter Hyams’ 2010: The Year We Make Contact. The admission of figuring out how to follow up Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey — while knowing they will not be able to match it — gives the sequel an underdog polish.

Still, I can’t resist going back to the chapters in which the interviewees fall flat on their face. After bad-mouthing his own Blade Runner, producer Bud Yorkin shares why audiences will line up ’round the block for his arms-dealing Chevy Chase vehicle: “People will come to see Deal of the Century because it’s a subject that is on the tip of everyone’s tongue. … The chase between the drone and something we call an F-19 will be a French Connection ride in the sky.”

Still, I can’t resist going back to the chapters in which the interviewees fall flat on their face. After bad-mouthing his own Blade Runner, producer Bud Yorkin shares why audiences will line up ’round the block for his arms-dealing Chevy Chase vehicle: “People will come to see Deal of the Century because it’s a subject that is on the tip of everyone’s tongue. … The chase between the drone and something we call an F-19 will be a French Connection ride in the sky.”

Pretty embarrassing, huh? Wait, Deal supporting actor Vince Edwards has something to add: “I think this film is going to be a blockbuster. The best damn picture since Dr. Strangelove. No, it’s going to be better.”

Thank you, Mr. Goldberg, for documenting the joy of hype and bullshit. —Rod Lott

A couple of years ago, the three-part documentary Time Warp: The Greatest Cult Films of All Time hit digital and underwhelmed me by covering all the usual suspects in such short bursts, it offered little new information or insight.

A couple of years ago, the three-part documentary Time Warp: The Greatest Cult Films of All Time hit digital and underwhelmed me by covering all the usual suspects in such short bursts, it offered little new information or insight.

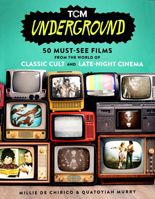

When Turner Classic Movies announced a companion book to TCM Underground, its long-running Friday-night showcase of the similar, I was leery it would be another round of the same well-worn territory. Now that it’s here — TCM Underground: 50 Must-See Films from the World of Classic Cult and Late-Night Cinema — I can happily report I needn’t have worried. Not only do its writers come prepared with plenty of insight, but they include a few movies I’ve never heard of, such 1976’s The Pyramid, a New Age slice of hippie-dippie WTF-ery.

In his foreword, comedian Patton Oswalt (whose movie-minded memoir, Silver Screen Fiend, is a must-read itself) puts readers in the proper mindset by asking them to rethink the requirements for inclusion: “Any movie that punches through the fog of worry, distraction, and ego that we’re stuck in creates a cult, even if it’s a cult of one adherent,” he writes, emphasis mine.

Flicks under discussion are divvied among five categories, from the genres of crime and horror to more nebulous looks at the family unit, rebellion and “mind melters.” The one concession to every other cult-movie list is Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Beyond that, the heavily illustrated entries — each either four or six colorful pages, all smartly designed by Josh McDonnell — cut a wide swath: Jigoku, Roller Boogie, Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, The Garbage Pail Kids Movie, Shack Out on 101.

Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization docs make up a full 6% of the content. One among the 50 is actually a 10-minute short, Curtis Harrington’s The Wormwood Star. Is that cheating? I’ll allow it. Deep cuts like that go a long way in endearing co-authors Millie De Chirico and Quatoyiah Murry to the reader. So do their compliments like “it all feels like a disjointed, cocaine-fueled splatter of spaghetti thrown against the wall,” which help mitigate the sting of a couple of factual errors — the most egregious stating Brad Pitt’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood performance “earned him his first Oscar win.”

Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization docs make up a full 6% of the content. One among the 50 is actually a 10-minute short, Curtis Harrington’s The Wormwood Star. Is that cheating? I’ll allow it. Deep cuts like that go a long way in endearing co-authors Millie De Chirico and Quatoyiah Murry to the reader. So do their compliments like “it all feels like a disjointed, cocaine-fueled splatter of spaghetti thrown against the wall,” which help mitigate the sting of a couple of factual errors — the most egregious stating Brad Pitt’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood performance “earned him his first Oscar win.”

Until hosting this trip into Late-Night Cinema, De Chirico and Murry were both new to me. And I’m glad, because I brought no preconceived notions to the book, other than good vibes toward the TCM Underground brand. Now, I feel like I know them well. They share particular affection for Michael Parks, blaxploitation, William Castle and obscurities released (unleashed?) by Something Weird Video and Vinegar Syndrome. They call Mary Woronov and Paul Bartel “the Doris Day and Rock Hudson of B movies.” People who think like that are friends to me, maybe even family. And you’ve gotta support your friends and family. —Rod Lott

The prolific crime novelist began his professional writing career as many scribes do: at the college paper. Whereas I had to report on the facility management department at the University of Oklahoma, Goldberg leveraged UCLA’s ink to write about his first love: 007, if you haven’t guessed by now.

The resulting interviews and articles from those pages — as well as Starlog, Cinefantastique and Prevue magazines — come collected in the slim, but satisfying The James Bond Films 1962-1989: Interviews with the Actors, Writers and Producers.

Four consecutive outings make up the bulk of the 120-page paperback: the “unofficial” Sean Connery comeback, Never Say Never Again; Roger Moore’s final outing, A View to a Kill (a set visit to which kicks off the contents); and both Timothy Daltons, The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill.

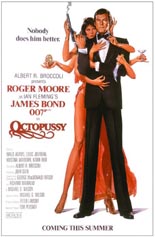

However, the best chapter involves none of the above. It’s an interview with Richard Maibaum, screenwriter of much of the franchise since its ’62 start. On the eve of Octopussy’s release, Maibaum redefines “candid” by trash-talking everything from the one-liners and scripts he didn’t write to, heck, leading man Roger Moore! I have no idea what Maibaum was thinking (or drinking?), but with such self-bloviating, I’m surprised producer Albert R. Broccoli didn’t can him. It’s the kind of interview studios wouldn’t let happen in today’s environment of fanboy-baiting paid junkets. (Journalism is dead, folks.)

However, the best chapter involves none of the above. It’s an interview with Richard Maibaum, screenwriter of much of the franchise since its ’62 start. On the eve of Octopussy’s release, Maibaum redefines “candid” by trash-talking everything from the one-liners and scripts he didn’t write to, heck, leading man Roger Moore! I have no idea what Maibaum was thinking (or drinking?), but with such self-bloviating, I’m surprised producer Albert R. Broccoli didn’t can him. It’s the kind of interview studios wouldn’t let happen in today’s environment of fanboy-baiting paid junkets. (Journalism is dead, folks.)

Goldberg unearths another massive ego when he interviews George Lazenby, the infamous one-time Bond, still with a huge chip on both shoulders. By contrast, the other one-timer, Barry Nelson — the first onscreen 007, thanks to a 1954 live TV presentation of Casino Royale — has the right attitude. So does regular screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, who correctly dubs the Bond series as “the Rolls Royce of action films.”

Goldberg’s book is quite a time capsule for James Bond fans, offering glimpses at select films through major creative talents. What it’s not is a front-to-back narrative, so don’t expect that; do expect a little repetition, necessary for piece-by-piece context — these are reprints, after all. Being a sucker for the 007 movies, I regularly buy books about them … only to usually emerge disappointed. That’s not the case with The James Bond Films 1962-1989, thanks to Goldberg’s access, insight and skill, approaching the work as one should: a writer first, a fan second. —Rod Lott