My introduction to vaulted film critic André Bazin, co-founder of the influential and revolutionary Cahiers du Cinéma, arrived as yours should: via The Cinema of Cruelty, Arcade Publishing’s trade-paperback reprint of the 1975 text collected and edited by François Truffaut, who knew something about the medium himself.

My introduction to vaulted film critic André Bazin, co-founder of the influential and revolutionary Cahiers du Cinéma, arrived as yours should: via The Cinema of Cruelty, Arcade Publishing’s trade-paperback reprint of the 1975 text collected and edited by François Truffaut, who knew something about the medium himself.

Both Frenchmen, the director and his subject were unofficial members of a mutual appreciation society, but Cruelty finds Bazin, who died in 1958 at the age of 40, discussing six other legendary filmmakers: Erich von Stroheim, Carl Dreyer, Preston Sturges, Luis Buñuel, Akira Kurosawa and Alfred Hitchcock.

The latter makes up the bulk of the material, which is great for two reasons:

1. Hitchcock is my favorite director.

2. Hitchcock is not Bazin’s favorite director. In fact, the film theorist wasn’t exactly into him at all, at least not at first. Because Truffaut presented select essays and reviews Bazin penned on the master of suspense chronologically, we have the pleasure of witnessing Bazin’s slow progression from disdain to being won over.

Seriously, this is to the degree Bazin’s dislike began (italics added for emphasis): “Since 1941, Hitchcock has contributed nothing essential to cinematic directing. Mentioning his name along with that of Orson Welles or William Wyler (which I have also been guilty of doing) as one of the principal champions of Hollywood’s avant-garde, stems from an illusion, a misunderstanding, or a breach of trust. … But just between us, we’ve been had.”

When Bazin finally came around, it was to praise 1953’s I Confess, oddly enough, which most of the world considers minor Hitch at best.

However, I’d argue that such unpopular opinions — call them “quirks,” if you wish — help made Bazin unique and cement his global reputation. The man clearly harbored undying love for the art form, then still in somewhat of an infancy, and his passion is reflected in lines like, “If Buñuel made films exactly as he wished, the screen would undoubtedly burst into flames at the first screening!”

While I dislike the occasional style of “Now I will address this …” guideposts, there’s no denying his status as a giant in the field. He was an important voice silenced too soon, and The Cinema of Cruelty was and remains an important book that I hope wins him new fans — beyond myself, mind you. —Rod Lott

Tim Hensley’s

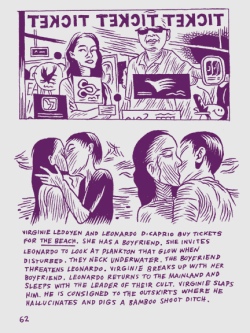

Tim Hensley’s  The scenes Hensley illustrates are not iconic; they appear to be chosen as haphazardly (if “chosen” is the correct term) as the films, which range from highbrow to lowbrow, classic to trash, beloved to obscure,

The scenes Hensley illustrates are not iconic; they appear to be chosen as haphazardly (if “chosen” is the correct term) as the films, which range from highbrow to lowbrow, classic to trash, beloved to obscure,