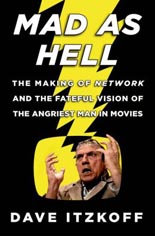

Yes, the subtitle of Dave Itzkoff’s Mad as Hell promises a behind-the-scenes chronicle of Sidney Lumet’s Network. Yes, the reader gets that, but the author delves deeper than that, to the point of telling not just the making of the 1976 film, but its conception, release, impact, blowback, legacy and continuing influence.

Yes, the subtitle of Dave Itzkoff’s Mad as Hell promises a behind-the-scenes chronicle of Sidney Lumet’s Network. Yes, the reader gets that, but the author delves deeper than that, to the point of telling not just the making of the 1976 film, but its conception, release, impact, blowback, legacy and continuing influence.

Part of that is because the book is as much as story about Network‘s celebrated screenwriter, Paddy Chayefsky, as it is about the Oscar-winning movie. A magnificent writer of television, stage and screen, Chayefsky was also an incredible control freak who ironically had no control over his family life; he clearly cared more about the written word than his flesh and blood.

Always waiting for the other shoe to drop, Chayefsky could not ever truly enjoy his incredible success — Network would bring him his third Academy Award for screenwriting — and harboring a near-extreme paranoia couldn’t help matters; he believed a second Holocaust was imminent. Nevertheless, he was able to function to do his job, starting with his much-abhorred boob tube. But it was film we forever will associate him with, especially the one with which Itzkoff’s book is concerned.

Network, we know now, was prescient — and continues to be more so as the years tick by — and even in scenes that never made it past the page, which Itzkoff details. One such case I found astounding is when the UBS execs dream up programming that is supposed to be considered wild: a show adapted from The Exorcist and a soap about homosexuals. We already have the latter; the former is being developed.

That’s one of many juicy bits the Mad as Hell reader will learn, thanks to Itzkoff’s judicious digging. Others include the revelation that Peter Finch could not complete two takes of “the” speech, that Lumet considered firing Faye Dunaway well after filming had begun, the pronunciation error that the to-the-letter Chayefsky failed to catch, and how Ned Beatty lied his way into a role. (I’d include how Dunaway did her damnedest to alienate most everyone, but everyone already knows that.)

If you haven’t seen Network — first off, shame on you — do not read this book until you do. Those who have may not want Mad as Hell to end, particularly knowing the fate of a reinvigorated Finch before the film could be fêted as that year’s Oscars. Only in a coda examining how Finch’s Howard Beale character has given rise to the likes of Glenn Beck does Itzkoff — turning from storyteller to social critic — produce a paragraph that’s not intensely readable. —Rod Lott