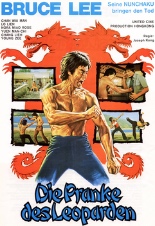

According to this Lee-alike flick, before he died, Bruce Lee wrote a book about how to kill people using only your fingers. Like the ghouls they are, the criminal underworld wants a copy of it so bad that they go as far as to kidnap Lee’s ex-girlfriend.

According to this Lee-alike flick, before he died, Bruce Lee wrote a book about how to kill people using only your fingers. Like the ghouls they are, the criminal underworld wants a copy of it so bad that they go as far as to kidnap Lee’s ex-girlfriend.

It’s up to a young martial artist — luckily named Bruce Le — to not only find the book, but rescue the girlfriend as well. He does this using not only public domain (?) clips of Lee, but masterfully by going from San Francisco for five minutes and then switching to another movie in Hong Kong after the credits and then to another one in, I think, Taiwan. With plenty of fights in open fields and courtyards, the book … is never really discovered.

I guess no one noticed that black-and white composition book peeking out from under the couch over there?

While Bruce’s Deadly Fingers really is, for the most part, your standard Bruce Lee death-curse rip-off flick, the one area of true maliciousness where the scummy nature of the film shines is when the assorted mob types torture the various girls who don’t wish to hook their bodies, including one mildly graphic scene with a deadly snake. It’s a scene where I could’ve used Bruce’s deadly fingers to poke my own eyes out. —Louis Fowler

For me, at least,

For me, at least,

One of the

One of the