I spend very little time with video games, but when I do, it’s Tetris. The play gets so ferocious that I later have stressful dreams about maneuvering its falling pieces. Turns out, this is perfectly natural — a problem shared by many of the Tetris-obsessed gamers profiled in the documentary Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters.

I spend very little time with video games, but when I do, it’s Tetris. The play gets so ferocious that I later have stressful dreams about maneuvering its falling pieces. Turns out, this is perfectly natural — a problem shared by many of the Tetris-obsessed gamers profiled in the documentary Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters.

As a narrator informs us, two out of three Americans have played the game. This causes Portland resident Robin Mihara to wonder why the world’s arguably most-played game doesn’t have a world champion? Director Adam Cornelius’ camera follows Mihara as he locates and assembles the best blockers for a proper Tetris championship event.

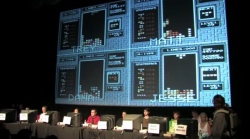

The contestants include a woman who wears a Mercedes hood ornament around her neck, a guy whose strategy entails making his eyes veer in separate directions and, most notably, the enigmatic Thor Aackerlund, who won a national Nintendo championship at the age of 14 and since claims to have cracked the game’s fabled level 30, yet has offered no photographic proof. Watching them square off against one another raised my pulse.

The contestants include a woman who wears a Mercedes hood ornament around her neck, a guy whose strategy entails making his eyes veer in separate directions and, most notably, the enigmatic Thor Aackerlund, who won a national Nintendo championship at the age of 14 and since claims to have cracked the game’s fabled level 30, yet has offered no photographic proof. Watching them square off against one another raised my pulse.

The obvious comparison to Ecstasy of Order is 2007’s The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters, the documentary about dueling Donkey Kong champs — so obvious, in fact, that it’s name-dropped by one of the players. But Ecstasy lacks that work’s Billy Mitchell, an arrogant bully to keep conflict and drama at a breathless high. In this doc, there are no villains; everyone’s a Steve Wiebe. That keeps Ecstasy from being as delirious entertaining as King of Kong, but makes it a natural for a second half of a double feature … because if you run it first, you’re just going to want to play Tetris, guaranteed. —Rod Lott

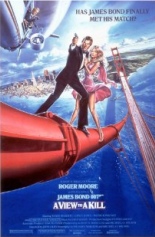

Roger Moore’s seventh go-round as James Bond doubled as his last, and proof that it was time for him to go occurs almost immediately in

Roger Moore’s seventh go-round as James Bond doubled as his last, and proof that it was time for him to go occurs almost immediately in

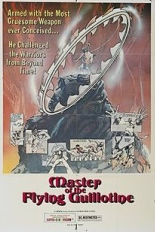

Jimmy Wang Yu’s

Jimmy Wang Yu’s

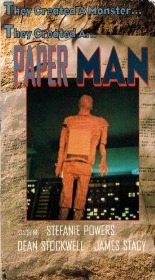

In

In