Of all the wavering output of the early 1970s independent studios, most of the Apple Films catalog have been the hardest movies to find. Usually, I have to go for bootlegs, downloads and other shady dealings.

That’s strange, because it was part of the Beatles’ far-reaching Apple Corps, a freewheeling production company investing in records, books, electronics, and numerous Pop Art items that have filled the dumpsters of time. In the end, Apple Corps was a good deal gone bad, with really only the music remaining. Apple Films’ only big hit was Yellow Submarine, maybe also Let It Be. Other films like Born to Boogie and The Concert for Bangladesh are essentially forgotten.

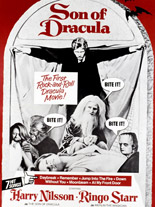

Which brings me to Son of Dracula, the apparently world’s “First Rock-and-Roll Dracula Movie!” according to the advertisements. It’s a take on the vampire mythos starring songster Harry Nilsson and ex-Beatle Ringo Starr, who also produced. But that’s not the most surprising thing about this — instead, this is: It was produced by Jerry Gross, the guy behind Mondo Cane, Teenage Mother and The Black Godfather. The father of the backbeat and the father of cinematic slime, together again!

One dark and ultimately confusing night, Count Dracula is assassinated by an unseen hand and his midget friend. Afterward, Merlin (Ringo Starr, in perhaps a prequel/sequel to Magical Mystery Tour?), the guardian of the netherworld, is summoned to his vampiric concubine to give birth to an immediate scion.

A hundred years later, Nilsson’s new count, Count Downe —ugh — comes to town in a stylish motorcar wanting a lay of the land. After going over some astrological charts with Merlin, he heads to Piccadilly Circus, performs a rousing cut of “At My Front Door” for the bar patrons and, appropriately, sucks the blood of the buxom maiden. So far, so good!

In case you were wondering, the backing band has Ringo on drums, as well as rock luminaries Peter Frampton, Leon Russell, Keith Moon and John Bonham. Where was that supergroup in the early ’70s and beyond? That’s the movie I’d like to see.

Son of Dracula instead shows Count Downe wanting a life-changing operation to make him a mere human. He does it, of course, to find his one true love. To mark the occasion, Downe has a party, with his hit song “Jump in the Fire” riding up the charts and heating up my speakers. During his preliminary operation, Dr. Van Helsing pulls Downe’s vampire teeth and commits other somewhat-laughable tortures.

This is where the movie loses me: Frankenstein’s monster attacks the Count, aided by a werewolf, a black cat, and, once again, a midget, for, I’m guessing, some revenge plot that seems to try everything while doing nothing. Look, by this time, I don’t know what’s happening, but the music is really good! True to form, it’s truly top-notch, top-shelf and above-board, as it should have been.

Directed by famed cinematographer Freddie Francis, the story and screenplay, the production values and the very bad acting — Nilsson’s nonexistent on-camera talent should live without you — is why most audiences avoided this in droves.

While Dracula and Frankenstein fanatics are not in any way clamoring for this home release, Son of Dracula has never been distributed on any home media format, leaving Beatles completists and Nilsson apologists in the lurch. It’s not very good, but I’d take a big box set with a pristine copy of the film, a 180-gram vinyl soundtrack and other associated memorabilia, like a swatch of Count Downe’s cape to make our own solo-Ringo dreams come true. While we’re at it, how about getting Ravi Shankar’s Raga reissued for my own personal edification … please? —Louis Fowler