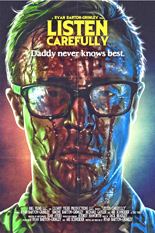

Listen Carefully is one of those indier-than-indie productions in which the creator’s name appears 10 times in the end-credits crawl — not out of ego, but sheer necessity. The problem that poses is often twofold: That person spreads himself too thin or simply isn’t proficient enough to handle their own assignments.

Ryan Barton-Grimley is neither. The multihyphenate proves dexterous on all sides of the camera, including front-and-center as Andy, a harried assistant bank manager at home with his infant daughter while his wife (Barton-Grimley’s real-life spouse, Simone) enjoys an evening out. When Andy awakes from a few accidental Zs, his baby has vanished from her crib. She’s been kidnapped, and the voice (Ari Schneider of his boss’ Hawk and Rev: Vampire Slayers) beaming through the baby monitor demands a cash ransom of $250,000 — from as many ATMs around Santa Clarita as it takes.

Like the most memorable “one crazy night” movies, from After Hours to Miracle Mile, the movie thrives on an ability to relay tension straight to the viewer. Listen Carefully does just that, as Andy undergoes every parent’s worst nightmare. Although siring children is hardly a prerequisite to enjoy this thriller, I felt Andy’s frustration exacerbated with the peculiar insecurities of a first-time father.

Although I wish Listen Carefully provided a wider range of crazy characters for Andy’s encounters, Barton-Grimley isn’t interested in dark humor as much as he is elements of sleep-deprived horror. His protagonist’s Kafkaesque ordeal is wound tight enough to resemble a Gordian knot. In a way, it is one, since Barton-Grimley’s script takes an out versus delivers an end. Still, the steps to get there form a nerve-rattled journey alive with the energy and danger of the night. It’s a can’t-miss premise, so don’t! —Rod Lott