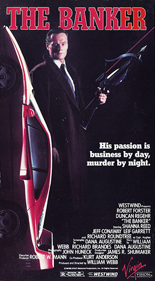

Prostitution’s a tough gig, even for Santa Monica’s finest. You might contract an STD or, per The Banker, a laser-guided crossbow arrow through the noggin. Even if the film didn’t reveal right away that titular man o’ finance Spaulding Osbourne is the killer, we’d know it because he lives in a warehouse, watches a wall of 16 television sets and keeps a Little Golden Book of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on his coffee table.

Prostitution’s a tough gig, even for Santa Monica’s finest. You might contract an STD or, per The Banker, a laser-guided crossbow arrow through the noggin. Even if the film didn’t reveal right away that titular man o’ finance Spaulding Osbourne is the killer, we’d know it because he lives in a warehouse, watches a wall of 16 television sets and keeps a Little Golden Book of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on his coffee table.

On the other hand, he has one redeeming quality: no love for cocaine bros in bolo ties.

Hunting Osbourne (Duncan Regehr, The Monster Squad’s Count Dracula) is police detective Sgt. Dan Jefferson (Robert Forster, Jackie Brown). It’s only a matter of time before Osbourne targets Jefferson’s ex-wife, TV reporter Sharon (Shanna Reed, TV’s Major Dad), who’s recently ditched segments promoting the Magic Sandcastle Jamboree for on-air editorials against the murderer.

Luckily for the good guys, Osbourne leaves a calling card at each homicide: a blood pattern on the wall that looks kinda like Wilson the volleyball from Cast Away. As Jefferson tells his lieutenant (Richard Roundtree, 1971’s Shaft), “We’re looking at one strange son of a bitch!”

William Webb’s directorial follow-up to the ho-hum Party Line, The Banker hums along nicely. It certainly helps going from Leif Garrett (who cameos here) to Forster. In a variation of his role in Alligator, Forster’s Dan is likely an alcoholic and lives in a treehouse. This allows Forster to give what he was so gifted at: a gruff, no-nonsense demeanor. Dana Augustine’s screenplay aids and abets with appropriate dialogue, including the concluding anti-quip, “I’m Dan, I’m a cop and you’re fucked!”

All in all, The Banker is the type of sleaze that’s polished just enough that you don’t feel a need to shower afterward. Who could’ve guessed that in 1989, Forster was less than a decade away from a career-reviving Academy Award nomination? Or that Roundtree would end the millennium returning as the iconic cat that won’t cop out when there’s danger all about? Or that former Playboy centerfold Teri Weigel and her Tupperware breasts were about to turn to porn? Or that Jeff Conaway could still run? —Rod Lott

Until

Until

Judging by the viral noise on TikTok — a terrible way to live, IMHO — you’d expect the $15,000-funded

Judging by the viral noise on TikTok — a terrible way to live, IMHO — you’d expect the $15,000-funded