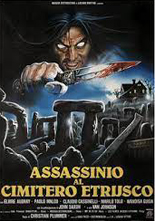

As is de rigueur with the giallo, the title is meaningless. But The Scorpion with Two Tails is no giallo. It’s more like Jell-O, but if director Sergio Martino didn’t bother reading the recipe, so the result fails to cohere. It’s a mess that falls apart almost instantly.

As is de rigueur with the giallo, the title is meaningless. But The Scorpion with Two Tails is no giallo. It’s more like Jell-O, but if director Sergio Martino didn’t bother reading the recipe, so the result fails to cohere. It’s a mess that falls apart almost instantly.

Joan (Elvire Audray, Ironmaster) is plagued by nightmares of an ancient Etruscan cult killing its members in a cavern filled with dry ice. The cult members wear full masks seemingly donated by Dumb Donald from the Fat Albert cartoon. These visions might have something to do with her archeologist husband (John Saxon, Cannibal Apocalypse) studying ancient whatnot in an Etruscan cemetery at that very moment. If only he were killed while sharing this info with Joan on the phone, we would know for sure.

He is killed while sharing this info with Joan on the phone, not even 11 minutes into the movie. So she has no choice but to investigate what happened to him, what’s happening to her and what her wealthy asshole of a father (Van Johnson, Concorde Affair ’79) has to do, has to do with it.

Martino being Martino (Torso, The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh, American Rickshaw, et al.), more murders occur; the film has more neck-twisting than the average chiropractor’s weekly appointment book.

Reportedly, Two Tails is edited down from an eight-hour miniseries. I cannot fathom watching this at that length, because what’s here amounts to so little action and other items of interest. We get slithering snakes, phony bats and, memorably, Joan’s hands swarming with real maggots. To be honest, I got more anxiety from the sheer amount of tiny Styrofoam beads thrown about as Johnson frantically searches for a vase by tearing open crate after crate. Cleaning up said beads requires more effort than Scorpion’s script received. —Rod Lott

It’s amusing to see viewers of

It’s amusing to see viewers of

Finnish director Jalmari Helander already has one modern cult classic under his belt with 2010’s twisted Christmas fantasy

Finnish director Jalmari Helander already has one modern cult classic under his belt with 2010’s twisted Christmas fantasy

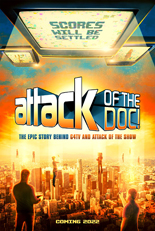

G4, I hardly knew ye.

G4, I hardly knew ye.