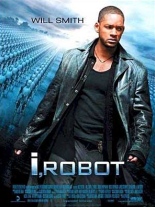

I, Robot: Me, unimpressed. You, better off doing something else.

I, Robot: Me, unimpressed. You, better off doing something else.

In a very loose adaptation of Issac Asimov’s classic book, I, Robot imagines a futuristic world 30 years from now, where friendly, eager-to-please robots are members of every household; where one miswired robot is suspected of murder; and where an entire robot revolution can be squashed by a wisecracking, sweet potato pie-eating cop in a skullcap and Converse sneakers.

That would be Will Smith, as Det. Spooner (a character not in the book, fork you very much), a homicide cop investigating the apparent suicide of a prominent robot inventor at the office of U.S. Robotics. All signs point to a new-model robot with the high-tech name of Sonny, although no robot has ever committed a crime before, being programmed with three laws which state, in essence, that no robot may ever harm a human; that a robot must obey human orders, as long as it doesn’t harm humans; and a robot must protect its own existence, also as long as it doesn’t harm humans. (These rules, unfortunately, do not extend to the audience.)

I, Robot doesn’t have a bad premise, just bad execution. My main problem with this movie lies with a miscast Smith. Continuously walking with a rap-video swagger, he has two modes of acting, each inappropriate: In normal situations, he’s over-the-top and shouting, while in times of life-threatening danger, he’s suddenly under the spotlight at Catch a Rising Star, lobbing leftovers from his Men in Black II quipbook. These ineffectual attempts at comedy include such one-liners as “Aw, hell, no!,” “Get off my car!” and — well, this is new — “Hold my pie!”

I, Robot doesn’t have a bad premise, just bad execution. My main problem with this movie lies with a miscast Smith. Continuously walking with a rap-video swagger, he has two modes of acting, each inappropriate: In normal situations, he’s over-the-top and shouting, while in times of life-threatening danger, he’s suddenly under the spotlight at Catch a Rising Star, lobbing leftovers from his Men in Black II quipbook. These ineffectual attempts at comedy include such one-liners as “Aw, hell, no!,” “Get off my car!” and — well, this is new — “Hold my pie!”

But he’s not the only actor to blame. As robot psychologist Dr. Susan Calvin, model-turned-actress (in theory, at least) Bridget Moynahan is quite robotic herself, and looks to be on the verge of tears with every line reading. The best performances come from the robots, and they’re computer-generated. In fact, there are times in this movie where everything onscreen is computer-generated, turning I, Robot into, quite literally, a cartoon.

Gifted director Alex Proyas (Dark City, The Crow) doesn’t help matters, forever swirling his camera as if it were a gyroscope, killing all sense of perspective in the action scenes and nearly requiring a dose or two of Dramamine. All he’s done here is created yet another megaexpensive sci-fi film with big, dumb moments out of place for the antiseptic tone he initially sets. I can see the script meetings now: “And the explosion will hurl Will out of the house, only he won’t get hurt because he’ll use a door like a surfboard and land safely in the pond outside! And he’ll do this while saving a kitty!” In keeping with Hollywood blockbuster mentality, all feats of derring-do are filmed in slow motion, all plot points are telegraphed far in advance, and all people unloading shotguns do so with lips pursed in a scowl. —Rod Lott

If anything,

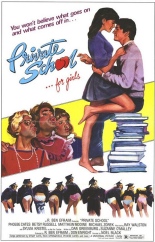

If anything,  The question, then, is why such a truly terrible teen comedy that only ever works as a desperate parody of itself succeeded when Black’s other films didn’t? The answer is simple: Betsy Russell riding topless on a horse. If you’re a heterosexual male between the ages of 30 to 40, you probably “watched” this scene at least a dozen times before you moved out of your parents’ house. And if you didn’t, you likely live a life of constant turmoil and regret.

The question, then, is why such a truly terrible teen comedy that only ever works as a desperate parody of itself succeeded when Black’s other films didn’t? The answer is simple: Betsy Russell riding topless on a horse. If you’re a heterosexual male between the ages of 30 to 40, you probably “watched” this scene at least a dozen times before you moved out of your parents’ house. And if you didn’t, you likely live a life of constant turmoil and regret.

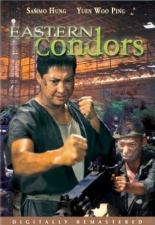

I’m not a fan of war movies, but leave it to Hong Kong to make one well worth watching. Sort of like a cross between

I’m not a fan of war movies, but leave it to Hong Kong to make one well worth watching. Sort of like a cross between  Those who do make it find immediate action, in a flick jammed full of it — and largely gory! — ranging from a dude getting stabbed right in the taint or another blowing up after having a grenade shoved in his mouth to your more standard, everyday decapitations and dismemberments. Although armed with machine guns, the men get inventive when it comes to defeating their enemies; Sammo even uses leaves to fell the bad guys by sending them flying through their necks.

Those who do make it find immediate action, in a flick jammed full of it — and largely gory! — ranging from a dude getting stabbed right in the taint or another blowing up after having a grenade shoved in his mouth to your more standard, everyday decapitations and dismemberments. Although armed with machine guns, the men get inventive when it comes to defeating their enemies; Sammo even uses leaves to fell the bad guys by sending them flying through their necks.

Building a hotel over one of the seven gateways to Hell will come back to bite you in the ass. So will bringing home a woman with milky eyes and a German shepherd, especially if you meet them standing motionless in the middle of the road. These and other lessons, director Lucio Fulci imparts with torn parts in his splatter horror classic

Building a hotel over one of the seven gateways to Hell will come back to bite you in the ass. So will bringing home a woman with milky eyes and a German shepherd, especially if you meet them standing motionless in the middle of the road. These and other lessons, director Lucio Fulci imparts with torn parts in his splatter horror classic  Melding two beloved fright-film subgenres — the zombie movie and the haunted-house thriller — Fulci’s The Beyond goes way beyond the horror norm, testing audience’s tummies with an triple-eye-gouging, face-melting, head-impaling, throat-tearing, forehead-penetrating, cheek-puncturing good ol’ time. The practical effects are grossly realistic, except for one point where some fakery is obvious. However, that’s the part where several tarantulas slowly crawl onto a paralyzed guy’s face and tear it apart, claiming the honor of being cinema’s all-time sickest spider scene. Arachnophobes will flip.

Melding two beloved fright-film subgenres — the zombie movie and the haunted-house thriller — Fulci’s The Beyond goes way beyond the horror norm, testing audience’s tummies with an triple-eye-gouging, face-melting, head-impaling, throat-tearing, forehead-penetrating, cheek-puncturing good ol’ time. The practical effects are grossly realistic, except for one point where some fakery is obvious. However, that’s the part where several tarantulas slowly crawl onto a paralyzed guy’s face and tear it apart, claiming the honor of being cinema’s all-time sickest spider scene. Arachnophobes will flip.

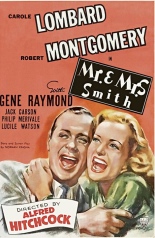

He didn’t. Mr. and Mrs. Smith is a standard screwball comedy with the requisite farce being that the title characters learn they were never legally married. When Ann Smith (Lombard) decides that that’s all for the best and that she doesn’t want to get remarried, David (Robert Montgomery) has to woo her all over again. The problem is in courting someone who already knows all his faults.

He didn’t. Mr. and Mrs. Smith is a standard screwball comedy with the requisite farce being that the title characters learn they were never legally married. When Ann Smith (Lombard) decides that that’s all for the best and that she doesn’t want to get remarried, David (Robert Montgomery) has to woo her all over again. The problem is in courting someone who already knows all his faults.