With the much-awaited No Time to Die just

With the much-awaited No Time to Die just a few weeks several months away from hitting theaters, the flood of 007-related books has begun, with none more desirable than Nobody Does It Better: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of James Bond. If you’re familiar with co-writers Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross’ previous treatments on Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, you know what you’re in for: a real wrist-strainer! But also your money’s worth — and then some. From Forge Books, the 720-page behemoth takes the reader through the making of all the Bond films, one by one — yep, even those deemed unofficial — using interviews from the actors, filmmakers and fans. The latter group can offer the occasional bit of fluff, like this contribution from Spy Kids papa Robert Rodriguez in full: “I love James Bond movies.” Wow, what insight! (Note that weird bit of italics, too — a practice carried throughout as if “James Bond” were part of the films’ titles … which they are not.) Other than that, Miss Moneypenny, the book is almost as much fun as a roll in the hay with Pussy Galore.

The story of the late Burt Reynolds can be told through the man’s filmography: He paid his dues (TV’s Gunsmoke), became a star (Deliverance), achieved box-office superstardom (Smokey and the Bandit), squandered it with baffling vanity vehicles (Stroker Ace), paid his dues again (Breaking In), landed a comeback with his finest role (Boogie Nights) and squandered it with baffling choices all over again (Cloud 9, anyone? Anyone?). Okay, so there is more to it than that, which I leave to Wayne Byrne, who spells it all out in Burt Reynolds on Screen. This retrospective of Reynolds’ career takes a chronological look at the legendary actor’s work on screens large and small, from the bit parts to big hits to roughly a decade and a half’s worth of movies you’ve never heard of. While each entry stands on its own, a full read paints a richer picture as Byrne is concerned not with synopses, but critiques of the work and considerations of their time in Reynolds’ life. Sprinkled throughout are interviews with a few former co-workers, but don’t expect Loni or Sally; the biggest names belong to Rachel Ward and Bobby Goldsboro.

The story of the late Burt Reynolds can be told through the man’s filmography: He paid his dues (TV’s Gunsmoke), became a star (Deliverance), achieved box-office superstardom (Smokey and the Bandit), squandered it with baffling vanity vehicles (Stroker Ace), paid his dues again (Breaking In), landed a comeback with his finest role (Boogie Nights) and squandered it with baffling choices all over again (Cloud 9, anyone? Anyone?). Okay, so there is more to it than that, which I leave to Wayne Byrne, who spells it all out in Burt Reynolds on Screen. This retrospective of Reynolds’ career takes a chronological look at the legendary actor’s work on screens large and small, from the bit parts to big hits to roughly a decade and a half’s worth of movies you’ve never heard of. While each entry stands on its own, a full read paints a richer picture as Byrne is concerned not with synopses, but critiques of the work and considerations of their time in Reynolds’ life. Sprinkled throughout are interviews with a few former co-workers, but don’t expect Loni or Sally; the biggest names belong to Rachel Ward and Bobby Goldsboro.

Many years ago, renegade filmmaker Alex Cox (Repo Man) wrote an embarrassing, half-assed book about spaghetti Westerns. Hey, don’t shoot the messenger! Those are his own words, right on the back cover to this, the second edition of 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director’s Take on the Italian Western; with the benefit of 30 years having passed, Cox has updated the book to add entries, alter opinions and correct errors (but didn’t catch them all, cries one “Gordon Herschell Lewis”). As published by Kamera Books, the paperback is more compact and reader-friendly than the heavier edition of the past. What’s not changed? Cox’s enormous passion for these pictures, which carries over to the reader, whether he’s discussing Dashiell Hammett’s influence on the genre, the transgressive violence of Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars, Terence Hill and Bud Spencer as the Italian Laurel and Hardy, or the terrifying prospect of Peter Bogdanovich nearly directing Leone’s Duck, You Sucker! Speaking not only as a fan but a filmmaker, his insight is more interesting — and entertaining — than the average bear: “Why does a producer do such things? Why does a dog lick his balls? Because he can.” —Rod Lott

Many years ago, renegade filmmaker Alex Cox (Repo Man) wrote an embarrassing, half-assed book about spaghetti Westerns. Hey, don’t shoot the messenger! Those are his own words, right on the back cover to this, the second edition of 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director’s Take on the Italian Western; with the benefit of 30 years having passed, Cox has updated the book to add entries, alter opinions and correct errors (but didn’t catch them all, cries one “Gordon Herschell Lewis”). As published by Kamera Books, the paperback is more compact and reader-friendly than the heavier edition of the past. What’s not changed? Cox’s enormous passion for these pictures, which carries over to the reader, whether he’s discussing Dashiell Hammett’s influence on the genre, the transgressive violence of Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars, Terence Hill and Bud Spencer as the Italian Laurel and Hardy, or the terrifying prospect of Peter Bogdanovich nearly directing Leone’s Duck, You Sucker! Speaking not only as a fan but a filmmaker, his insight is more interesting — and entertaining — than the average bear: “Why does a producer do such things? Why does a dog lick his balls? Because he can.” —Rod Lott

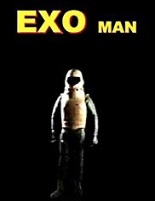

Remember the first-act origin of

Remember the first-act origin of  Good thing the doc’s been experimenting on how to alter the structure of matter — or something like that. All that matters is he succeeds — depicted through the not-so-special effects of magnets under the table — which enables him to “walk” again. To justify the title, he constructs a protective suit that makes him look like an unholy blend of a Shop-Vac and Conky from

Good thing the doc’s been experimenting on how to alter the structure of matter — or something like that. All that matters is he succeeds — depicted through the not-so-special effects of magnets under the table — which enables him to “walk” again. To justify the title, he constructs a protective suit that makes him look like an unholy blend of a Shop-Vac and Conky from