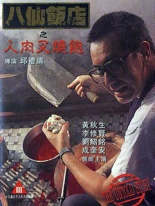

There was a time in Hong Kong cinema when Category III flicks about insanely graphic serial killers were all the rage, with The Untold Story one of the best remembered and most award-winning, which is completely surprising to me because — and let’s be honest — it’s kind of terrible.

There was a time in Hong Kong cinema when Category III flicks about insanely graphic serial killers were all the rage, with The Untold Story one of the best remembered and most award-winning, which is completely surprising to me because — and let’s be honest — it’s kind of terrible.

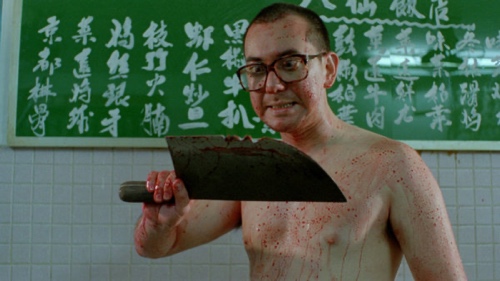

Directed by Herman Yau with all the skill and dexterity of a low-budget TV-movie journeyman, Story stars a skin-crawling Anthony Wong as the untold storyteller, a glasses-wearing creeper with a boiling-over penchant for ultraviolent outbursts, one of which luckily takes him to exotic vacation destination Macau.

But, as you can guess, that’s really only half of the untold story.

Once there, he opens a restaurant that specializes in the best steamed pork buns in town, absolutely filled with the perfectly cooked meat of the previous night’s kill. City on Fire’s Danny Lee, who seems to always have a hooker on each arm, leads an investigative squad of buffoonish cops only interested in ogling Lee’s women while simultaneously eating free pork buns and harassing the only woman on their team, mostly for not having heaving breasts.

After years of destructive desensitization, the grue and gore aren’t really all that shocking, with the exception of the brutal scene where Wong uses a handful of chopsticks in a way they were hopefully never intended for. While the last half of the movie mostly features Wong constantly beaten while in police custody, in scenes that might give a few fascist viewers untold boners, I’m really not sure what was the point.

With a little urine drinking — according to Wong, it helps heal your busted-out, broken-down innards — the film’s abrupt ending, complete with a Dragnet-styled voiceover, only adds to the back-alley greasiness of the cleaver-heavy proceedings, a dirty job that won Wong the Best Actor trophy at the Hong Kong Film Awards. —Louis Fowler

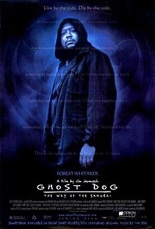

I’ll gladly admit that I was a pretentious sixth-grader who regularly rented and fully enjoyed the films of Jim Jarmusch.

I’ll gladly admit that I was a pretentious sixth-grader who regularly rented and fully enjoyed the films of Jim Jarmusch.