Over the past couple of decades, I think we can all agree two of the best cinematic examples of total mind-fucks have been The Matrix and Inception, right? At least that’s what Entertainment Weekly told me recently.

Over the past couple of decades, I think we can all agree two of the best cinematic examples of total mind-fucks have been The Matrix and Inception, right? At least that’s what Entertainment Weekly told me recently.

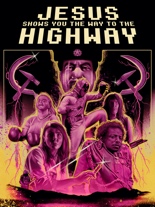

That being said, I’m pretty sure the Ethiopian flick Jesus Shows You the Way to the Highway has them both beat and beaten badly with intense imagination and general weirdness that puts those multimillion tentpoles to increasing shame with each subsequent viewing.

In the far future of a retro world, Special Agent Gagano (deformed actor Daniel Tadesse) is assigned to virtually enter the Psychobook — this universe’s version of the Internet — and try to stop the destructive computer virus called the Soviet Union. After a double-cross or two, Gagano finds himself trapped in the dusty mainframe.

Traveling through the virtual world of New Ethiopia, the pizza-loving Gagano continually tries to wake up and find his way back to his wife, a blonde giantess, to keep his promise of helping her open a kickboxing academy. As an Irish-accented Stalin and corrupt hero Batfro try at every turn to stop him, once he realizes the power of the world he’s in, he becomes unstoppable, with the help of the titular Jesus.

I think.

Expat director Miguel Llanso, cherry-picking from the best (worst?) of 1970s pop culture, from Filipino kung-fu to dystopic Philip K. Dick novels, has crafted a beautifully tacky world for his cast to play in, with the enigmatic Tadesse doing most of the surreal heavy lifting. Jesus is Afro-futurism sci-fi at its best, a future awash in the flotsam of the past and the jetsam of an unpredictable psyche. —Louis Fowler

Flint, Michigan’s renowned coronary specialist, Dr. James Arnold (Cal Seely), could be having a better week. The international medical community is skeptical of his research into heart transplants. His molasses-slow elderly benefactor, Mrs. Woodruff (Roz Kramer), is threatening to freeze funds if she doesn’t see results before her heart sputters out. And back home, his coulda-been-a-contender brother, Tom Arnold (!), is allowing his rentable tramps to raid the doc’s liquor cabinet.

Flint, Michigan’s renowned coronary specialist, Dr. James Arnold (Cal Seely), could be having a better week. The international medical community is skeptical of his research into heart transplants. His molasses-slow elderly benefactor, Mrs. Woodruff (Roz Kramer), is threatening to freeze funds if she doesn’t see results before her heart sputters out. And back home, his coulda-been-a-contender brother, Tom Arnold (!), is allowing his rentable tramps to raid the doc’s liquor cabinet.

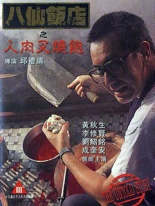

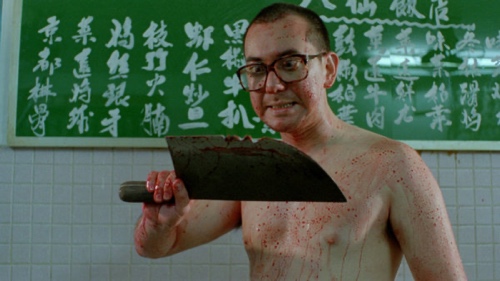

There was a time in Hong Kong cinema when Category III flicks about insanely graphic serial killers were all the rage, with

There was a time in Hong Kong cinema when Category III flicks about insanely graphic serial killers were all the rage, with

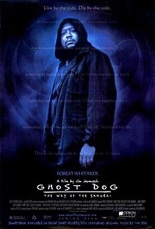

I’ll gladly admit that I was a pretentious sixth-grader who regularly rented and fully enjoyed the films of Jim Jarmusch.

I’ll gladly admit that I was a pretentious sixth-grader who regularly rented and fully enjoyed the films of Jim Jarmusch.