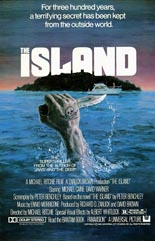

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water, Jaws producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck returned to plumb the then-shallow well of Peter Benchley novels for another round of ocean-set thrills. The result was The Island, so waterlogged it’s hardly worth even thinking about. Not one moment approaches the spine-tingling suspense promised by the film’s nerve-shattering poster.

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water, Jaws producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck returned to plumb the then-shallow well of Peter Benchley novels for another round of ocean-set thrills. The result was The Island, so waterlogged it’s hardly worth even thinking about. Not one moment approaches the spine-tingling suspense promised by the film’s nerve-shattering poster.

After 600 boats have vanished within three years in the Caribbean waters, magazine writer Blair Maynard (Michael Caine, who would later star, ironically enough, in Jaws: The Revenge) is dying to pursue the story. Because the divorced dad has his 12-year-old son (Jeffrey Frank, in his one and only feature) for the weekend, Blair tricks the kid into going to Florida with him by promising a trip to Disney World.

That never happens; instead, they get trapped in a real-life variation of the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction after crash-landing on an island — er, the island — where actual pirates separate Justin from his father, under the orders of their leader (David Warner, The Omen). While Blair is tortured with leeches, Justin is all-too-easily brainwashed into turning against dear Dad.

That never happens; instead, they get trapped in a real-life variation of the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction after crash-landing on an island — er, the island — where actual pirates separate Justin from his father, under the orders of their leader (David Warner, The Omen). While Blair is tortured with leeches, Justin is all-too-easily brainwashed into turning against dear Dad.

One method used to turn Justin is sleep deprivation, which is what the bulk of the film feels like. Boasting scenery galore, it’s nonetheless exceedingly dull and slow-moving. Director Michael Ritchie had a flair for comedy (Fletch, The Bad News Bears, Smile), not chills, but he can’t shoulder the blame for the biggest nonmoving part: the screenplay, penned by Benchley himself. It could use some Carl Gottlieb. —Rod Lott